Over the past year, the Museum of Islamic Art has digitalised the glass and plastic negatives and diapositives from the two excavation campaigns by the museum in Samarra (today: Iraq) in 1911-13.

In the Samarra Revisited exhibition, all of the 1500 or so preserved photographs have now been made accessible for the first time. Even the museum employees themselves were not fully aware of the portfolio.

This led to the idea of asking current and former employees to take a closer look into the digital reproductions. 24 participants chose five photographs from Samarra which touched on their areas of work. You can find each of their "favourite photos" with comments as a digital print in the exhibition. All the other digital reproductions chosen, and the reasons for their choice, are available in the media station.

This selection shows the wide spectrum of possible uses for excavation photographs: they help archaeologists and provenance researchers to locate sites - RESEARCH. They show that excavation photographers also endeavoured in the past to enable a comparison of their photographs with the originals - COMPARE. As the photographed site situations become lost forever as a result of the excavation work, the significance of photography must not be underestimated! However, the photos also act as links to current social discourses - QUESTIONING. They delight and inspire - JOY. Finally, the photos shown here document a formidable site of Islamic archaeology with a charm and appeal that has not been lost today - LOCATE.

UTE FRANKE, ARCHAEOLOGIST

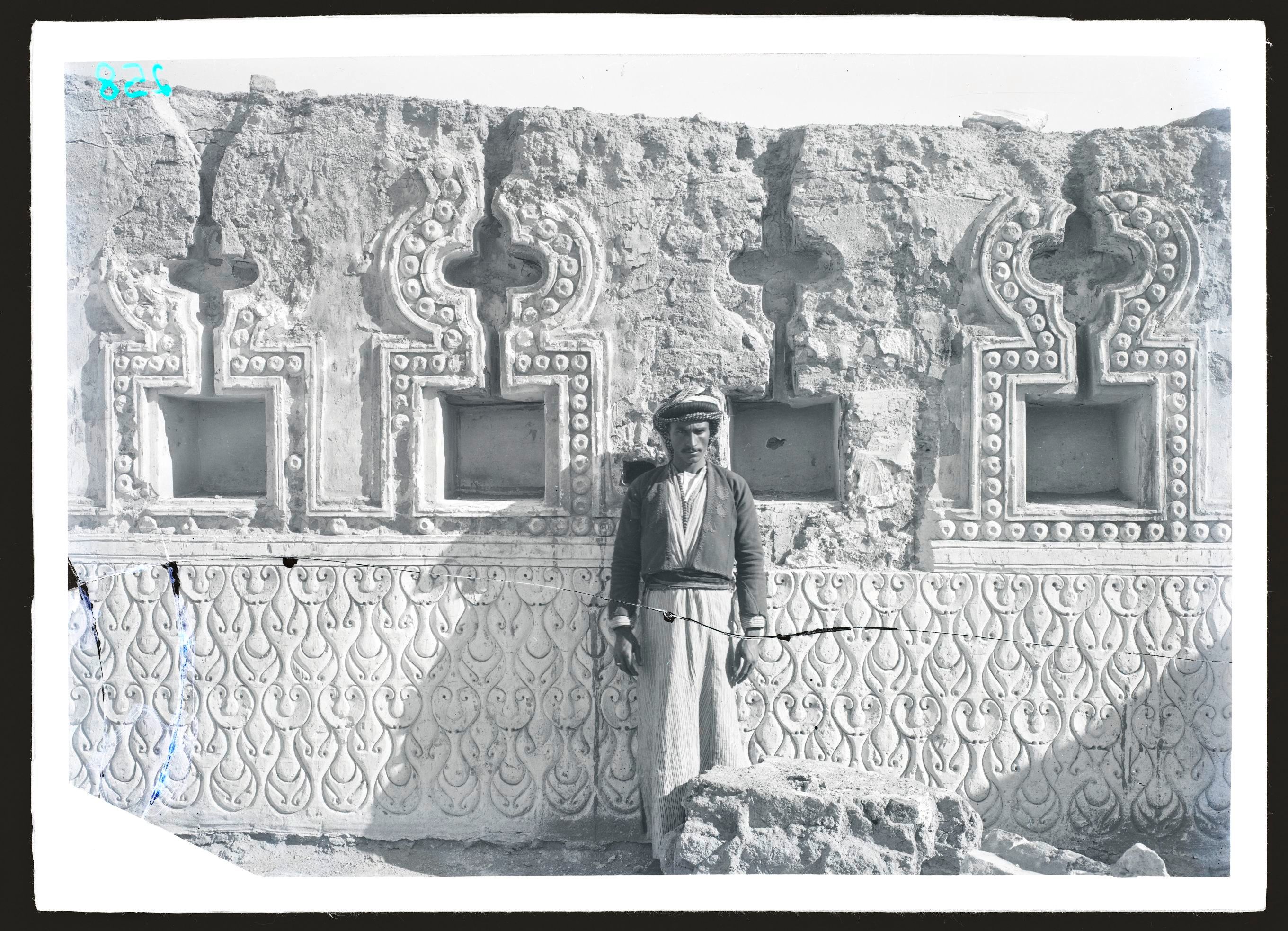

"From my perspective as an archaeologist, photos provide important insights into discovery situations. You can see four phases here in profile, one after the other: two brick walls on the brick floor, two layers of debris in between, another layer of rubble over that."

AN ARCHAEOLOGIST'S VIEW

The pictures are not documentary excavation photos, but they still show construction phases and layers if you look ver closely. Many labourers "dig" with hoes and clear away the rubble with trolleys, but paperwork for the findings and archaeologists cannot be seen. So the site has not been grouped by room or into separate layers. However, this was commonplace in 1911.

Besides the Islamic city, painted ceramics, also known as Samarra ceramics, from the 6th Century AD have also been found.

Both photographs are perspectives of the same situation: the flat profile of the mound shows construction and rubble layers, the stump in the middle shows earlier layers; the older floor beneath it has partially been removed and "search holes" created below.

Here you can see stone foundations at different heights, including brick structures and various walls, door passageways with debris and a water pipeline at the top.

STEFANIE JANKE, PROVENANCE RESEARCHER

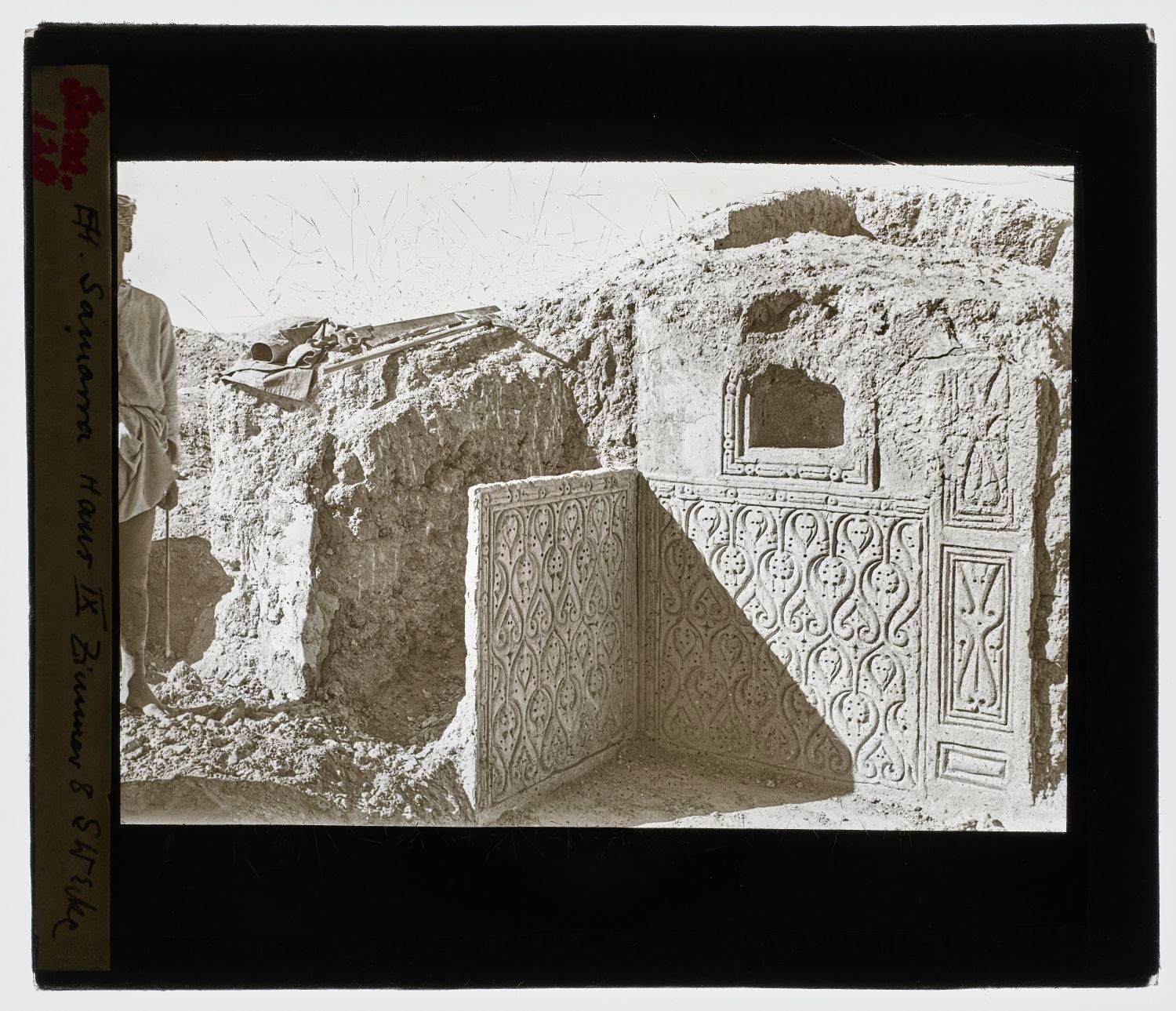

"Excavation photos provide information about the origins of objects and the excavation methods used at the time. The clay brick walls have been taken down here in order to remove the decorated stucco board.

Accompanying texts also provide valuable information for other researchers."

PROVENANCE RESEARCH AND EXCAVATION METHOD

From my perspective as an archaeologist and provenance researcher, it is important to be able to reconstruct the original discovery context of an object using photos. Naturally, in order to do this, I have to analyse the targets of the excavation and the questions it raises, and the excavation methods used at the time. For a system, I also need to know how the excavation documentation was arranged (e.g. by excavation complexes). The accompanying texts and reasons for the photos themselves also provide important information.

STORY ABOUT THE SPECIAL EXHIBITION "SAMARRA REVISITED"

Samarra Revisited

What actually happens behind the scenes in the museum? The special exhibition "Samarra Revisited - New Perspectives on the Excavation Photographs from the Palaces of the Caliph" opens a very personal insight of the employees into the museum work.