Over the past year, the Museum of Islamic Art has digitalised the glass and plastic negatives and diapositives from the two excavation campaigns by the museum in Samarra (today: Iraq) in 1911-13.

In the Samarra Revisited exhibition, all of the 1500 or so preserved photographs have now been made accessible for the first time. Even the museum employees themselves were not fully aware of the portfolio.

This led to the idea of asking current and former employees to take a closer look into the digital reproductions. 24 participants chose five photographs from Samarra which touched on their areas of work. You can find each of their "favourite photos" with comments as a digital print in the exhibition. All the other digital reproductions chosen, and the reasons for their choice, are available in the media station.

This selection shows the wide spectrum of possible uses for excavation photographs: they help archaeologists and provenance researchers to locate sites - RESEARCH. They show that excavation photographers also endeavoured in the past to enable a comparison of their photographs with the originals - COMPARE. As the photographed site situations become lost forever as a result of the excavation work, the significance of photography must not be underestimated! However, the photos also act as links to current social discourses - QUESTIONING. They delight and inspire - JOY. Finally, the photos shown here document a formidable site of Islamic archaeology with a charm and appeal that has not been lost today - LOCATE.

ANTONIA NAASE - MASTERS' DEGREE STUDENT

"What I like in particular about this photo in particularly is the way the working people are represented. The photographer photographs the workers in a respectful manner and they look back into his camera, smiling."

PEOPLE AS FOUND OBJECTS?

When I was recording discovery sites with the help of the blueprint collection, I was annoyed when I opened the "Types" folder. Unlike the other folders, this one had pictures of people in it. The people seem to be part of the scenery itself, as they have the same backdrop and are posed identically. At the same time, the photos are given an anthropological character by the presentation. The people have been documented in the same way as other groups of found objects. But this is not fair to the people in the photos.

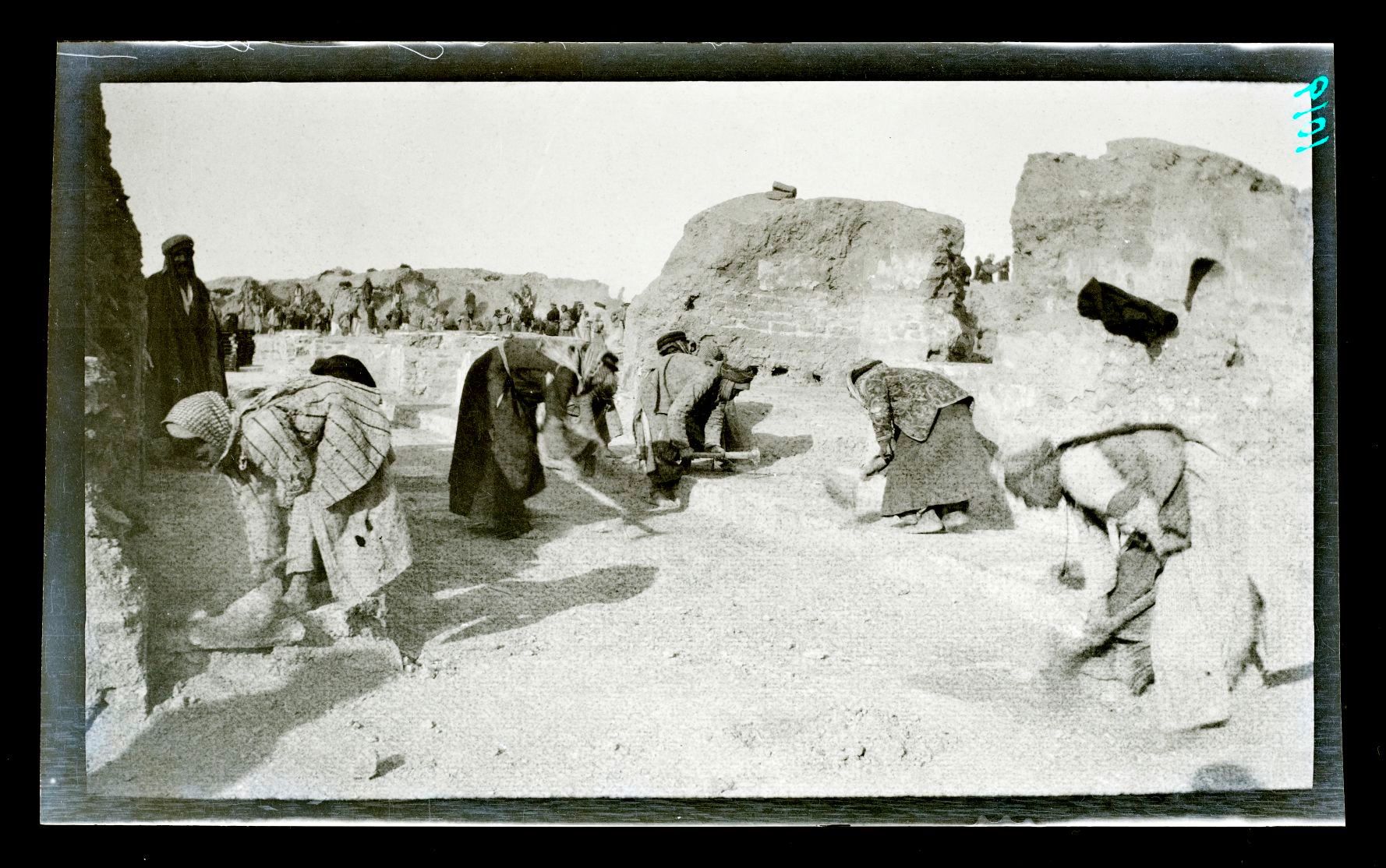

ANTONIA KRAPPE, VOLUNTARY SOCIAL YEAR

"I like the photos of the people who did not get the recognition they deserved, who worked on this gigantic project like "ants". Without them, it would have been impossible to uncover Samarra. The dimension of the excavation becomes even clearer through the juxtaposition of people and ruins. I like the photos of the people who did not get the recognition they deserved, who worked on this gigantic project like "ants". Without them, it would have been impossible to uncover Samarra. The dimension of the excavation becomes even clearer through the juxtaposition of people and ruins."

PEOPLE AND WORKING CONDITIONS

I am doing a voluntary social year here in the museum and have scanned blueprints of the Samarra photos. In many of the pictures, you can see people, animals and landscapes, like looking through a window that lets you see back into the past.

I would love to talk to the people, what they think about the excavations, if they worked there of their own free will and if they were treated well. Where they come from, if they have families and listen to what they talk to each other about.

CHRISTINE GERBICH & SUSAN KAMEL, MEDIATION/MUSEUM STUDIES

"This man represents the countless local labourers who contributed to the glory of European museums. Their names and contributions to the production of knowledge have been ignored for so long. How do we deal with this historic injustice today?"

PEOPLE BEFORE THINGS AND WORKING CONDITIONS

We are interested in the social and political issues of museum work. We therefore prioritise people over things. The pictures show the harsh working conditions on site. They throw up questions about the balance of power between local and European labourers. How high were the wages, how was the medical care? Who benefitted from local knowledge? Why were things given so much priority over people? And what effect do the pictures have today on people who come from the region?

STEFAN WEBER, DIRECTOR, MUSEUM FOR ISLAMIC ART

"A change of perspective with a nameless Iraqi. What would he say to us? Workers in excavations or building projects in Berlin or Samarra, yesterday or today, are still unmentioned. Is this normal, or a bad thing? Herzfeld's pictures have preserved the memory of some of these people."

THOMAS TUNSCH, CURATOR

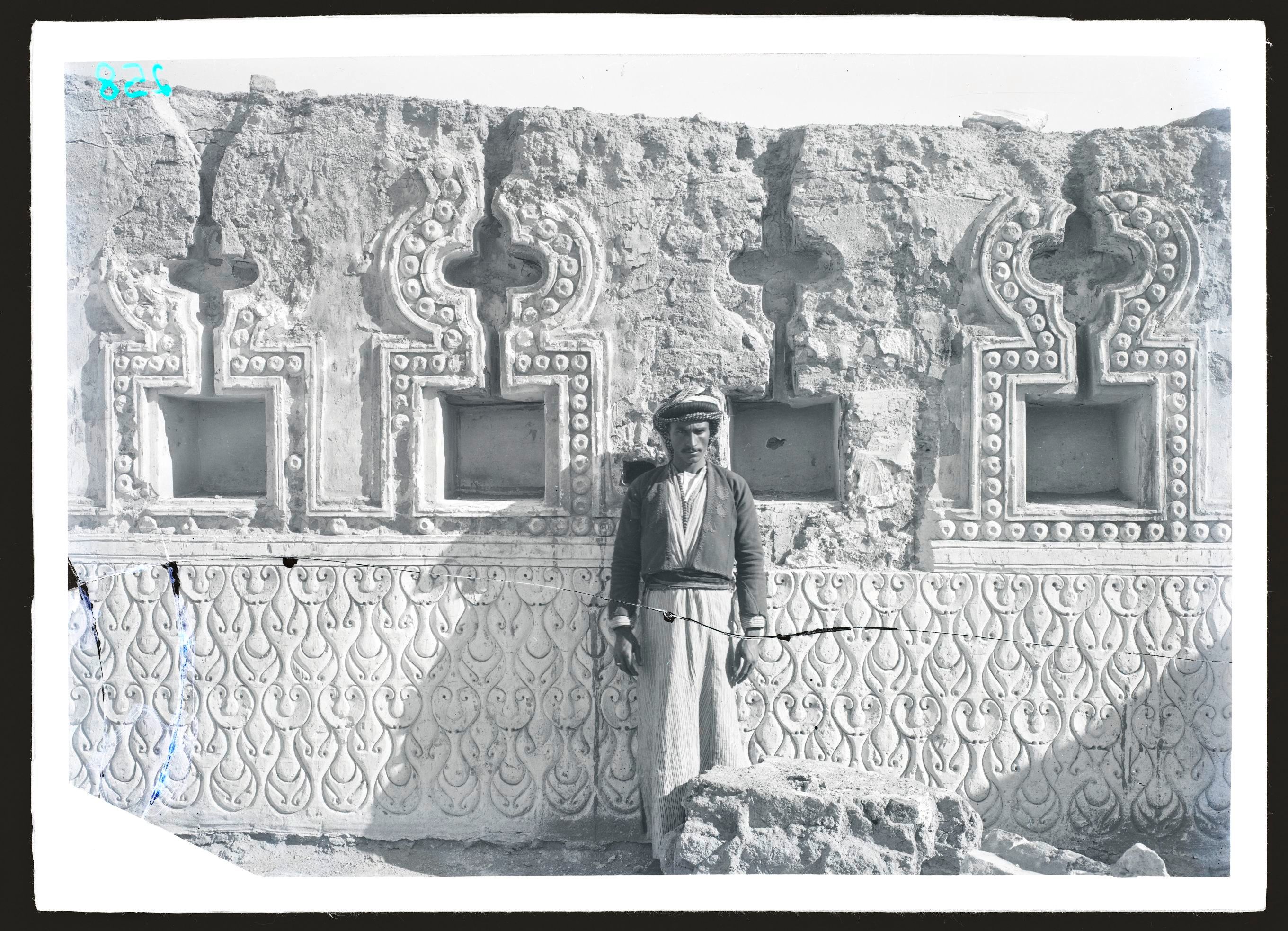

"The ephemeral magnificence and the contemporary portrait of the excavation worker with damages to the photo plate show important sides of the cultural heritage institution of the "museum". Each generation must decide for themselves what will be kept in it."

PEOPLE AND THE MUSEUM

On tours of the museum, I have pointed out the diversity of the patterns and the relationships with different cultures on the wall coverings from Samarra in the museum exhibition. For me, the collected objects are no longer the most important things in the museum anymore; instead, it is the stories of the people associated with them. Excavation photos of Samarra show people involved in publicly arranged poses as well as working, and even today, they bring the ruins to life.

ATEFEH KHERIRABADI, EXPERIMENTAL FILM MAKER

WORK AS A PROCESS

I am interested in work processes. In one photo, you can see a wall painting that shows a person holding a tool (?). In the other, women and children, who helped work on the excavation, with or without certain tools.

STORY ABOUT THE SPECIAL EXHIBITION "SAMARRA REVISITED"

Samarra Revisited

What actually happens behind the scenes in the museum? The special exhibition "Samarra Revisited - New Perspectives on the Excavation Photographs from the Palaces of the Caliph" opens a very personal insight of the employees into the museum work.