About this Photo exhibition

What did it mean to live among centuries-old monuments? In 1970s Cairo, historic buildings were part of daily life. People lived in them, worked in them, and built their communities around them. This quiet yet powerful reality is captured in this story which was originally presented as a photo exhibition in collaboration with the Museum for Islamic Art as part of the '20th Colloquium of the Ernst Herzfeld Society for Studies in Islamic Art and Archaeology', held for the first time in Cairo.

This photo exhibition highlights the daily life of Cairenes in Historic Cairo during the 1970s, showcasing one of the world's richest cities filled with Islamic monuments. The forty images are drawn from the Meinecke archive at the Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin, a collection created by the art historian Michael Meinecke (1941–1995) and his wife, the art historian Viktoria Meinecke-Berg (1941–2005). This exhibition aims to reveal a layer of history often overlooked, fostering a deeper understanding of the relationship between Cairo, its people, and visiting scholars while reflecting on the archive’s value for these discussions.

The Photo Exhibition is curated by Dr.-Ing. Eman Shokry Hesham (Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Max-Planck Institute) and Issam Al-Hajjar (Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin) and in collaboration with the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo.

Through Meinecke’s Lens

Michael Meinecke and his wife Viktoria Meinecke-Berg established their long-term connection to Egypt when Michael Meinecke joined the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo as a senior research fellow in 1968, a bond that remained strong even afterwards when he became the director of the Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin. Through Meinecke’s lens, we observe how Cairenes lived with and among Cairo’s monuments fifty years ago, featuring sites like houses, clinics, banks, society headquarters, and emergency shelters, illustrating the people’s sense of ownership.

Beyond documenting the state of the monuments, Meinecke captured sentimental moments with local inhabitants in their social context.

Street life and Traditions

Wikalas were common in Cairo during the Mamluk and Ottoman periods, playing a vital role in trade and commerce.

In the photo here are Wikala of Muhammadayn, also known as Khan Abu Taqiya al-Saghir (delisted from the index of the national registered monuments in 1957), and Wikalat Oda Bashi (below) represent several wikalas in Cairo built in the 17th and 18th centuries, 1977.

[A Wikala is a historical building that functioned as a commercial hub, providing spaces for merchants to store goods and reside.]

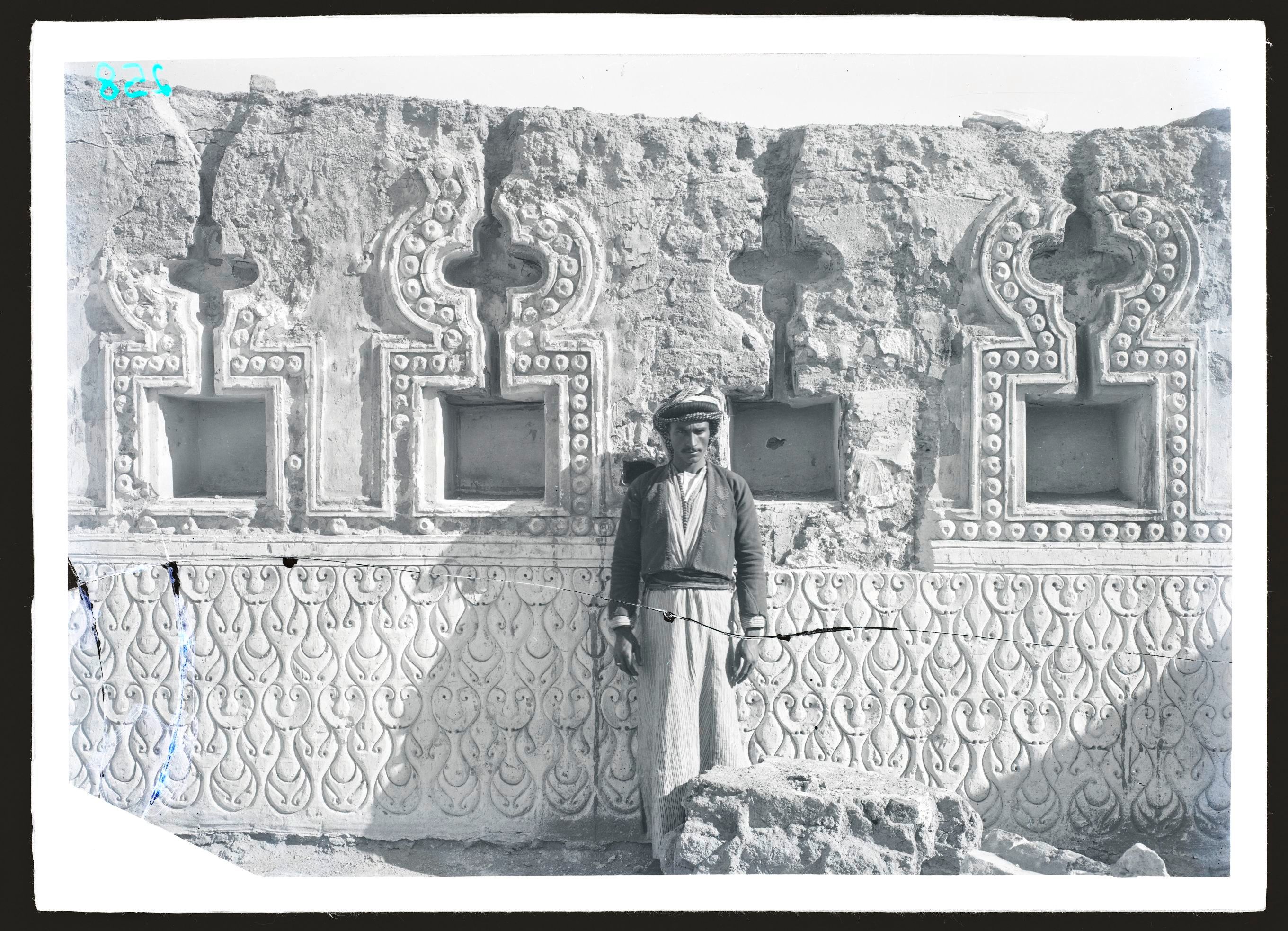

Wikala Kahla (wikala of Oda Bashi)

The wikala of Oda Bashi is also known as Wikala Kahla. The sign on the left door refers to the Arab Socialist Union, the leading political party in Egypt during Anwar al-Sadat's presidency, 1977.

Some wekalas built in Cairo during the 17th and 18th centuries, especially on the outskirts of the heart of Historic Cairo, as in Bulaq and al-Huseineih, still maintain the same function today.

This photograph depicts the façade before the intensive restoration, which concluded in 2002. As seen in another photo, the Arab Socialist Union took over several monuments in various districts of Cairo to serve as its local offices.

Reference: For more photographs and information on the wekala, its endowment deed, and a brief mention on its restoration, see M. Abul Amayem, Islamic Monuments of Cairo in the Ottoman Period III, Wekalas, Khans and Qaysaryas, part 1 (Istanbul 2015), 111–116, 343 f.

a historic street in Cairo

The bustling al-Muʿizz Street in Cairo with its various retail shops and passersby. The minaret of the complex of Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun dominates the background, 1977.

[Al-Mu'izz Street, is a historic street in Cairo, Egypt, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Founded by the Fatimid Caliph al-Muizz li-Din Allah, the street was once the grandest thoroughfare of the Fatimid capital, Al-Qahira.]

Al-Ashraf Street in the extended City of the Dead

Al-Ashraf Street is where several mausolea from the Fatimid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk periods are situated in the extended City of the Dead. The Mamluk mausoleum of Fatima Khatun Umm al-Salih (682–83/1283–84) with its minaret is in the background, while the ruins of al-Ashraf Khalil’s mausoleum (687/1288) are seen on the right, 1974.

Al-Ashraf Street literally means the street of the Nobles, as it is home to several mausolea of the Prophet Muhammad’s family members, or Āl al-Beit. Al-Khalifa Park, located just a few steps from where this photograph was taken, is one of several projects on this special street initiated by the Athar Lina Initiative to promote local social and economic development and investment in human resources.

Upper floors of one of the wikalas of the Mamluk Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay, behind al-Azhar mosque (882/1477), were used as a residential space. Two blazons of Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay are seen decorating the façade on the first-floor level, 1969.

licking a column with lemon juice for healing

This photo shows a corner column with a composite capital of the madrasa of Uljay al-Yusufi (447/1373), reused from an older structure. In Meinecke’s photograph (1972), the column is partially obscured by bricks and plaster. ʿAli Pasha Mubarak (lived 1824–1893) notes it was covered during the reign of Khedive ʿAbbas Hilmi I. (r.1848–1854) to prevent locals from licking it with lemon juice for healing. The grooves at the base are remnants of this practice. The plaster is now completely removed.

It is unknown if the column of the madrasa of Uljay al-Yusufi was part of the original structure of this part of the complex. The sabil and kuttab section, which this column supports its corner, is clearly a later addition in the Ottoman period. According to a restoration plaque, this part of Ulgay al-Yusufi’s complex was restored by Emir Mohammed Agha in 1046 H. ʿAli Mubarak mentions this column when talking about Haret Halawat. He attributes the column to the Uljay al-Yusufi mosque, also known by its local name, as-Sayies Mosque. At the beginning of this lane, there were two adjacent corners: One was known as Dargham's corner and the other as Bardak's, which are now gone.

‘There is a bluish pillar about two meters long (originally white), belonging to the as-Sayies Mosque, and above it is a school (Maktab) full of children. During the period of HH Muhammad ʿAli, some Moroccans noted that this pillar had an advantage that is said to have been tried and true; namely, that people with jaundice and other internal diseases come to it, anoint it with lemon water, and then lick it with their tongue, repeating the licking until black blood comes out of the tongue. If they use this method three times, they are cured, by God’s will. Thus, this pillar gained a reputation for this advantage, and many people used it continuously until the reign of the Khedive ʿAbbas Helmi I. (r.1848–1854). They were forbidden from using it, reportedly because men and women crowded around it. A thief noticed a woman wearing a lot of jewelry and attempted to take it, so he forbade anyone from approaching the column and ordered it to be covered with plaster. A few years later, some mosque servants uncovered the bottom of the column, built a wooden cupboard as tall as a man, and made a door that could only be opened for a fee. This practice continues to be known and utilized by many people today’.

Reference:

H. Abdul Wahhab, Tarikh al-Masajid al-Athariya I (Cairo: 1946), 189 f.

A. Mubarak, Al-Khitat al-Tawfikiya al-Jadida II, 2nd edition (Cairo: 2004), 290 f.

Functions of monuments

The portal of the wikala of Qaitbay or Khan Saʿid (before 902/1496), featuring visible late Mamluk decorations, is in Suq al-Bunduqaniyin in al-Hamzawi Street; a commercial site since the Bahri Mamluk period (648–923/1250–1384), 1978.

The area of l-Hamzawi is one of the densest areas in Historic Cairo with wekalas. To this day, it remains home to several retail shops and workshops. On the one hand, No. 15 in al-Hamzawi as-Saghir Street, as shown in this photograph, may refer to Wekala al-ʿAqabi, Khan al-Fasqiya (also known as Wekala al-Ibar), or Qisariyet Tashtumur, which was built in the 730s/1330s, according to Abul Amayem (delisted in 1933). On the other hand, this photograph could represent Khan Saʿid in the same street. Khan Saʿid may be a remaining part of Qaitbay’s two khans, shops, and several Rabʿ constructions in this area; these, too, were delisted when constructing al-Azhar street. The Latter suggestion is plausible, since the lintel stone decoration suggests the Late Mamluk style.

activities in the wikalas and their courtyards

The images show activities in the wikalas and their courtyards (here, the wikala and sabil of Waqf al-Haramain 1272/1856), 1977.

This photograph's registration number (433), referenced in the Meinecke archive, refers to the Sabil-Kuttab of Waqf al-Haramain. However, the photo possibly depicts the Wekala of Waqf al-Haramain (should be Nr. 598, also known as wekala an-Nakhla), which was registered in 1934 for the significant mosque built in its courtyard. However, in 1957, it was delisted. The mosque was demolished shortly after the wekala was delisted, as Meinecke's photo shows its semi-square courtyard packed with stored goods – possibly grain. The mosque only appears in archival plan drawings. Currently, the wekala houses metal workshops. Abul Amayem gives the date of construction of this wekala as 1079/1669.

Reference:

M. Abul Amayem, Islamic Monuments of Cairo in the Ottoman Period III, Wekalas, Khans and Qaysaryas part 1 (Istanbul: 2015), pp. 432 fn. 1, 334–373, 351–353.

the sabil-kuttab on al-Azhar Street

The sign at the side portal to the sabil-kuttab on al-Azhar Street describes this section of al-Ghuri complex (909–910/1504–1505) as the Society of Sayyidna al-Husayn for memorizing the Holy Qurʾan and facilitating the Hajj and ʿUmra. The kuttab likely served for Qurʾan memorization practice, while the sabil functioned as the society's office. No social society in Egypt currently holds this name, 1978.

[A "sabil-kuttab" is a charitable foundation in Islamic architecture that combines a sabil (a public water dispensary) and a kuttab (an elementary Quranic school for children).]

Tharwat Okasha, the Minister of Culture in Egypt (1958–1962, and 1966–1970), decided to establish the Popular Culture Organization in 1966 and opened several cultural centers in Egypt, all with presidential and governmental support. Okasha was so influenced by the Maisons des Jeunes et de la Culture, which belonged to the French Ministry of Culture, that he brought the idea back home after visiting France in the 1960s. Since 1989, the cultural centers have been under the jurisdiction of the General Organization of Cultural Palaces, while the Artistic Creativity Center at al-Ghuri mausoleum falls under the auspices of the Cultural Development Fund, both entities being overseen by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

Ghouri Centre of Culture

The mausoleum of al-Ghuri was used as a library of the ‘Ghouri Centre of Culture’, while other cultural centre activities took place at the khanqah of the complex, 1977.

Changing functions of the sabil of Qaitbay

The sabil of Qaitbay behind al-Azhar mosque (881/1477), as several photographs show, has served multiple functions since its original use diminished in modern times. The sign on the right indicates it was used as an elementary school called al-Jawhariyya. Another sign indicates the sabil is a local office of the Popular Resistance Leadership, 1969.

Directly opposite the sabil of Qaitbay is the al-Azhar Mosque, which houses the madrasa al-Jawhariya, constructed during the Mamluk period (844/1440). Another photograph in the Meinecke Archive (1977) shows that the same sabil was used, likely after the 1973 war, as the executive office of the political party, the Arab Socialist Union, in al-Darb al-Ahmar for the districts of al-Gharib and al-Mujawrin.

The Public Resistance was a critical movement whose existence had been associated with the war years in Egypt (1967–1973). ʿAbd al-Mohsin Abu an-Nur, the leader of the Public Resistance, withdrew from his responsibilities as Minister of Land Reclamation in June 1967 to dedicate his full time to leading the movement.

Changing functions of a sabil-kuttab

The sabil-kuttab of Abu al-Iqbal (1125/1713) had two functions in the 1970s. The ground floor likely served as a site for the Arab Socialist Union and the Executive Office of al-Darb al-Ahmar for the al-Batniyya district (as the sabil-kuttab of al-Ashraf Qaytbay behind al-Azhar mosque). The upper floor, originally a kuttab, became the al-Batniyya Medical Clinic, with a sign indicating the streets served by this clinic, 1973.

Temporary branch of Bank Misr

The sabil of Kosa Sinan (12th/18th century) overlooks al-Azhar and al-Husayn mosque from its location at the end of Harat al-Sanadiqiyya and enjoys a prominent position on al-Azhar street. Given the location, in front of al-Azhar Moqsue and beside al-Hussein Square, and its convenient interior space, the rationale for its temporary use for banking transactions is well explained, 1971

Al-Darb al-Ahmar Society for Family and Child Welfare took the takiya of Sultan Mahmoud (1164/1750) as its location, 1971.

[In Sufi tradition, "Takiya" can refer to the place where a spiritual leader or Murshid resides.]

A house from the Mamluk period in Cairo

This house is one of the few remaining from the Mamluk period in Cairo. Initially built by the granddaughter of al-Nasir Hasan in 1482, it has been named after the last owner, Zaynab Khatun, since 1125/1713. The Egyptian Ministry of Culture currently uses the house for cultural activities. The personal style of the owner in the 1970s prevails in hanging the image of the President at the time, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and keeping the old national flag above the piano in one bay of the qaʿa, 1972.

Built in the Late Mamluk period with additions in the eighteenth century, it shows medieval woodwork, decorations, medieval house divisions and planning, and eighteenth-century modifications. Besides this house's artistic and architectural significance, the Meinecke photos of the house's interior show only a phase of the tenant's political views. Zaynab Khatun played a national role in Egyptian history as she participated in the popular resistance against the French campaign in Egypt (1798–1801). Apparently, after the British military commander during the British occupation had lived in the house, the following tenant in 1972 still celebrated his support for the late Egyptian President Jamal ʿAbd an-Nasir (1956–1970) and the old national Egyptian flag that was changed in 1971. Plate V in the famous Jacques Revault and Bernard Maury’s publication Palais et Maisons du Caire du XIVe au XVIIIe siècle shows the same frame hanging on the wall and the same set of furniture in the qaʿa. In all the 110 plates or the residential houses featured in this publication, only plates III and V of Zaynab Khatun’s house show signs of a living space.

Reference:

J. Revault and B. Maury, Palais et Maisons du Caire du XIVe au XVIIIe siècle III (Cairo: 1979), 1–12, pls. I–VII.

The photo shows the interior of the sabil of sultan Mustafa III. (1173/1759 ), which has served as the location of the Society of the Holy Quran Recitation. The interior was equipped to accommodate this service with additional cupboards and comfortable seating, 1977. The sabil, including the interior, was renovated in the 2010s.

kuttab space

This Meinecke photo shows the upper floor of ʿAbd al-Rahman Katkhuda's iconic sabil-kuttab (1157/1477) at al-Muʿizz Street with desks, proving that the kuttab space had been an educational venue for over two centuries, 1972.

social and political climate on the streets of Egypt from 1967 to 1973

Captured in 1969, this image reflects the intense social and political climate on the streets of Egypt from 1967 to 1973. ‘The hour of revolutionary action has struck’ is the intro of the graffiti written at the entrance of the mosque of Qaytbay in Qalʿat al-Kabsh (880/1475).

Al-Ahram, 26 December 1969 (issue 30331, p. 8), reiterates another one from al-Ahram, 27 October 1967 (issue 29540, p. 6). This suggests that danger was still anticipated in 1969 and arguably persisted until 1973:

‘The Ministry of the Interior has asked citizens to follow the following guidelines in the event of air raids.

If you are at home or inside any building, you must turn off the lights immediately and leave the windows open to prevent them from breaking. Turn off the stoves and shut off the water and gas valves. Do not leave your place during the raid; take refuge on the lower floors or basement. Avoid taking shelter in stairwells, as they are prone to collapse. Avoid using the telephone. in case they are damaged or the power is cut off. If you are on the street, leave your car or tram and head to the nearest shelter or refuge. If you are in a car loaded with flammable materials, the driver should move it to an open area away from residential areas. In coastal areas, care should be taken to avoid exposing lights.’

public shelter

‘Makhbaʾ ʿāmm’, or ‘public shelter’, is a sign seen on several monuments in the Meinecke archive, including this one, the mosque of Timraz al-Ahmady (876/1472). All of the photographs that have these signs were taken before 1973.

A photo in the K. A. C. Creswell photo archive at K.A.C. Creswell Papers and Photograph Collection of Islamic Architecture, Rare Books and Special Collections Library, American University in Cairo, from the 1940s shows a sign that says ‘Abri No. 423’ in French, and ‘makhba ‘am Raqam 423’. The sign fixed at the corner of the As-Salih Tala’i mosque is a rare visual evidence of the official use of registered and newly restored monuments in Cairo during the 1940s as public shelters from air raids during World War II, especially after the German and Italian forces targeted Alexandria and Cairo, causing some casualties.

The Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l'Art Arabe (1881–1961) had finished a comprehensive restoration of the mosque As-Salih Tala’i in 1915.

References:

E. A. Helal, ‘Egypt’s overlooked Contribution to World War II’, in: The World in Wars: Experiences, Perceptions and Perspectives from Africa and Asia (Leiden: 2010), 217–247.

A. Patricolo, ‘VII. Mosquée d'as-Sâlih Talâyi' (555 H. = 1160 A. D.)’, Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l'Art Arabe, Fascicule 32, exercice 1915–1919, 1922, 40–42, doi: https://doi.org/10.3406/ccmaa.1922.15532.

A. al- Sayyed, F. R. H. Darke, P. Lacau, and E.Verrucci, ‘3° Mosquée d'as-Sâlih Talâyi'’, Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l'Art Arabe, Fascicule 33, exercice 1920–1924, 1928, 273–274, doi: https://doi.org/10.3406/ccmaa.1928.9684.

public shelter during the war

Another sign informs locals about the Makhbaʾ ʿamm, or the public shelter, during the war. This time, it was the wikala of Qaytbay at Bab al-Nasr (885/1480–81), 1970.

Amina Shafiq mentioned in an article in al-Ahram on 03 August 1969 (issue 3186, p. 6), one year before this photograph was taken, that sixty families had been living in this wekala of Qaitbay for two years after their houses were destroyed. These families might have moved from one of the canal cities that were bombed in 1969 to Cairo. This image includes another important visual material, besides the state of war and its associated function, which no longer exists. It shows a historical plaque. To the right of the entrance bay was a decree plaque, and it was still in situ. Max Van Berchem describes the plaque, which testifies to the public outrage in 886/1481, arising from rumors of minting new coinage with less weight than the original, necessitating an urgent meeting between Qaitbay and his emirs. After the meeting, it was decided that the old and new coins would be weighed to avoid fraud.

effects of war and the subsequent situation for the wikala and mosque of Taghri Bardi in al-Maqasis

The eight-year gap between these two images (left, 1970, and right, 1978) highlights the effects of war and the subsequent situation for the wikala and mosque of Taghri Bardi in al-Maqasis (10th/16th century). The arrow in the image (left) on the façade of the wikala points to the mosque, presumably where the public shelter was. The image (right) also showcases a new façade treatment.

Mohammed Abul Amayem believes the wekala of Taghri Bardi was built in the 17th century, a later period than the date registered in the national index.

References: M. Van Berchem, Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum XIX 1, Égypte III, 500, n°. 326, pl. XI, no. 1.

M. A. Ibn Iyas, Badaʾiʿ az-Zuhur fi Waqaʾiʿ ad-Duhur III, ed. Moḥammad Mustafa (Cairo: 1984), 189.

M. Abul Amayem, Islamic Monuments of Cairo in the Ottoman Period III, Wekalas, Khans and Qaysaryas part 1 (Istanbul: 2015), 312–317.

different uses of the complex of Khayrbak al-Ashrafi

This set of images also illustrates different uses of the complex of Khayrbak al-Ashrafi (908/1502) between 1970 (left) and 1974 (right). In 1970, the sign ‘public shelter’ was hung on the façade of the sabil, next to the main entrance. Shortly after the war, the complex became an office for the Civil Defense of the Arab Socialist Union in the Bab al-Wazir district. Additionally, presumably as a social activity of the ruling party, the office offered educational facilities for school students.

This piece of news from al-Akhbar newspaper from 29 August 1967 (issue 4732, p. 4), explains the meaning of Civil Defence, and indicates to us what type of service was offered at this location and the vision it was expected to achieve:

‘Cairo Secretariat discusses increasing savings and civil defence:

The Cairo Secretariat of the Socialist Union discussed the political action plan for the current phase at its meeting yesterday. Secretaries and members of the executive offices in Cairo attended the meeting. The plan included strengthening the economy by increasing savings, developing Popular Resistance and Civil Defence, protecting the revolution from counter-revolution, working to eliminate the effects of aggression, reducing consumption by achieving the goals of the production plan, the need for workers to work hard to earn more hard currency, exposing various forms of exploitation in trade and social relations, and reducing ostentatiousness, extravagance and privileges imposed by the nature of work, solving the problems of the masses, cooperating with the executive bodies, increasing educational services and practicing self-criticism at all levels while adhering to spiritual values.’

Monuments as Material Resources of History

Several images depict the art historian Viktoria Meinecke-Berg, the wife of Michael Meinecke, taking notes, examining the interior, or sketching a schematic plan for the monuments. Meinecke-Berg contributed to the Meinecke archive and authored various publications on Islamic architecture in Egypt, 1972.

notable scholars in Islamic architecture, archaeology, and restoration in Egypt and the Arab world

The Meinecke Archive includes notes about scholars who collaborated with Michael Meinecke during his working time in Cairo. Common companions, besides Viktoria Meinecke-Berg, included ʿAbd al-Rahman ʿAbd al-Tawwab, Archibald George Walls, Christel Kessler, and Saleh Lamei Moustafa, who appears in this image. All are notable scholars in Islamic architecture, archaeology, and restoration in Egypt and the Arab world. Their collective fieldwork likely fostered productive discussions and outstanding scholarly contributions, 1969.

Actual State and Restoration Process

These images show restorations of the courtyard walls and floor at the madrasa of Mithqal al-Anuki (763/1361–62) in 1975.

This three-year restoration project (1973 to 1976) marked the first collaboration between the German Archaeological Institute Cairo and the Egyptian Antiquities Authority for a monument from the Islamic period.

the façade of Wikalat al-Rukn

The image displays a freehand sketch from 1977 by the art historian Archibald George Walls, created over a Meinecke photograph of the façade of Wikalat al-Rukn (built before 1800) in al-Muʿizz Street, a visual study of how it might have appeared, 1977.

DOCUMENTATION

The left image highlights the ever-changing boundaries of the al-Aqmar mosque since its construction (519/1125) and its strategic location, as it was directly connected to the Fatimid Eastern Palace. The photos show the façade in 1977, and the courtyard decorations on the arches (right, in 1970) in their state of preservation before the restorations in the late 1990s. One of the actions taken during restoration involved the expropriation of the houses encroaching on the southern side of the façade, which is still visible in the top-left photograph.

remains from the Fatimid structure

A man, perhaps the owner of the shop to the left, reveals what remains from the Fatimid structure, the Kufic foundational inscription of the zawiya of Jaʿfar al-Sadiq (496/1101), which was built during the reign of the Caliph al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah. This plaque in Kufi script is now at the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo (no.113), 1971.

This Fatimid plaque was the last piece of evidence for the mosque of Jaʿfar as-Sadiq, constructed by Prince Jawamurad al-Afdali, probably of Armenian origin (ʿOthman, p. 442), during the reign of the Fatimid Caliph al-Amir Biʾahkam-Illah (r. 495/1101–524/1130). The mosque has been delisted, and the plaque is no longer in place. ʿAli Mubarak says that locals used to celebrate the birth of Imam Jaʿfar in the area of the mosque.

The Imam Jaʿfar as-Sadiq, who died and was buried in al-Baqiʿ in 148/765. The text inscription states the dream narrative:

‘…The construction of this blessed mosque was ordered by Mawlana as-Sadiq Jaʿfar ibn Muhammad ibn ʿAli ibn al-Hussein ibn Abi Talib, peace be upon them, in a dream of his servant, the Amir and leader of the state, Jawamurad al-Afdali, in the year four hundred and ninety-five, and its construction was in the year four hundred and ninety-six.’

Faraj al-Husseini correlates this case with a phenomenon of building mosques and mausolea during the Fatimid period as a response to dreams of the Prophet Muhammad or members of his family, the descendants of Imam ʿAli.

Reference:

A. Mubarak, Al-Khitat al-Tawfīkiya al-Jadida II, 2nd edition (Cairo: 2004), 246.

F. H. F. al-Husseini, an-Nuqush al-Kitabiya al-Fatimiyia ʿAla al-ʿAmaʾir Fi Misr (Alexandria: 2007), 239 f, pl. 68, fig. 187.

M. A. ʿOthman, Mawsuʿat al-ʿImara al-Fatimiya: al-Harbiya, al-Madanyia, al-Diniya, part 1 (Cairo: 2006), 442.

Meinecke documents Social life in and around the Cairene monuments

Social life in and around the Cairene monuments has a rich share in the Meinecke archive within the architectural documentation process.

As we observe, in 1972, the camera bag resting open on a wooden bench inside the Sabil of Khayrbak al-Ashrafi (908/1502) (left), and in 1977, in front of the so-called sabat, or vaulted tunnel below the madrasa of Amir Mithqal (763/1361–62) (right), Meinecke documents the curious and playful children watching him work on site.

Other engagements with the locals are evident, where students and young Cairenes smile at Meinecke’s lens in front of the mausoleum of al-Gulshany (926–931/1519–1524) (right, 1969) and mosque of ʿAbd al-Latif al-Qarafi (10th/16th century) (left, 1977).

Ash-Shaikh Ibrahim al-Gulshani built the mausoleum and takiya complex between 1519 and 1524. The Façade of the mausoleum appears in the background and was covered by Ottoman ceramic tiles of various styles, origins, and periods. Those tiles were not part of the original façade's decorative scheme. Between 2011 and 2013, vandalism on this complex resulted in the loss of most of the tile decorations that appear in this photograph.

Related Stories

Samarra Revisited

What actually happens behind the scenes in the museum? The special exhibition "Samarra Revisited - New Perspectives on the Excavation Photographs from the Palaces of the Caliph" opens a very personal insight of the employees into the museum work.

Fragment No. 57

This fragment is part of the "CulturalxCollabs - Weaving the Future" carpet. Follow its journey through its ever changing owners' over three and a half years. Current Owner: Suzanne Zeidy

Fragment No. 88

This fragment is part of the "CulturalxCollabs - Weaving the Future" carpet. Follow its journey through its ever changing owners' over three and a half years. Current Owner: Mahy Mourad