en

- de

- en

About the Story

Understanding the origins and tracing the journey and ownership of objects in the collection is one of the core responsibilities of a museum. Through provenance research an object can be correctly attributed and we can learn a lot about the object’s cultural significance.

This tile, which is now in the collection of the Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin has travelled a long way in its history. Today, we think that it could come from a mihrab, the niche in a mosque that indicates the direction of Mecca (qibla), towards which Muslims pray, and that it was probably made in the workshops of Kashan. Kashan is a historic city in central Iran and was one of the most important and famous centers for lusterware production in the Islamic world, especially during the 13th to 14th centuries. However, its origins remained unclear for decades, with earlier theories suggesting a connection to Spain before scholars reevaluated its provenance.

Mihrab tiles like this one are found in many places like Varamin. This research was first published in “Tile in the form of an arch” Luster cabinet entry and was commissioned, edited, and designed for: The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine. It has been adapted for the Online-Portal Islamic·Art.

Tile from a mihrab

Tile with an arch, possibly from a mihrab

Iran, probably Kashan, 13th century

Original building unknown

Fritware molded, opaque white glaze, luster painting

28.6 x 27.1 x 4.2 cm

Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin, KGM 1900,26

Photograph © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Islamische Kunst / Christian Krug

Earliest Records of the Tile in the Museum

How did the tile enter the museum collection? In the spring of 1900, Julius Lessing (d. 1908), director of the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts) in Berlin, travelled to Spain. According to the museum’s inventory records of the Kunstgewerbemuseum (which are now publicly available), Lessing acquired seven works of art in Seville from a person named Schlatter. The oldest of these objects was this tile, listed in the inventory logs as ‘Tile, Spain, 14th century’. A pencil addition reading “Islam. Abtlg.” indicates that the tile was transferred to the Museum für Islamische Kunst at an unknown date.

Transcription: Fliese, gepresst und mit Lüstermalerei auf weißer Zinnglasur. Viereckiger Platte mit reliefiertem Spitzbogenfeld und Palmetten in den Zwickeln, mit Arabesken in Lüstermalerei überzogen. Spanien, 14. Jahrhundert. 1800 Pesos, Schlatter, Sevilla

Translation: Tile, molded and with luster painting on white tin glaze. Square plate with pointed arch field in relief and palmettes in the spandrels, covered with arabesques in luster painting. Spain, 14th century. 1800 pesos, Schlatter, Seville

View the inventory book of the Kunstgewerbemuseum online

Provenance research: Attribution of the Tile to Spain

The Zentralarchiv of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin describes provenance research with the following words:

“Provenance research interrogates how museum objects were collected, acquired and sometimes misappropriated, and shines a light on the often circuitous paths they took to end up in the museum. It deals with the contexts behind changes in possession and ownership, from the creation of an object to its inclusion in the collections. The work of provenance researchers highlights the forgotten stories behind the objects. These stories are almost always fascinating, but are sometimes also bizarre or shaped by violence.”

In our case, provenance research not only sheds light on where the tile was acquired, but also on the history of its attribution and exhibition.

When the first director of the Berlin Museum für Islamische Kunst, Friedrich Sarre (d. 1945), published an article on Spanish luster ceramics, he agreed with the initial conclusions of the tile’s attribution to Spain. In the article, Sarre observes a close stylistic relationship between the presumed ‘Spanish’ tile in Berlin and tiles in the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo in Granada. He also comments on similarities between the gold luster of the tiles. Sarre considers the Spanish origin of the Berlin tile to be proven: “I conclude that the presumed Persian origin of this tile can be ruled out” (Sarre 1903).

Questions about the tile’s attribution

Sarre’s successor, Ernst Kühnel (d. 1964), director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst 1931 to 1951 seemed less certain of tile’s attribution to Spain. In 1927, the tile was included in an exhibition of Islamic art at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague. In his review of the exhibition published in “Der Kunstwanderer”, Kühnel states, “It is not without reason that it has occasionally been claimed to be Persian, especially in view of the colour of the clay” (Kühnel 1927).

With the opening of the new permanent exhibition at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin in 1932, the tile entered the collection of the Museum für Islamische Kunst. A photograph taken in early 1933 shows the tile with other Persian luster tiles and pottery in a single showcase. It appears that Kühnel, who was responsible for the new exhibition, wanted to emphasise his Persian attribution.

The Contribution of a specialist

Jens Kröger, curator at the Museum für Islamische Kunst from 1985 until his retirement in 2007, published an interesting contribution in the online exhibition Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin. His article focuses on the travels of Friedrich Sarre to the Ottoman empire and Greater Persia from 1895 to 1900 to study the architecture and art of the Achaemenian, Parthian, Sasanian, and Islamic periods using material from our photograph archive.

Journey of the tile in Berlin

The journey of the tile from Kashan to Seville to Berlin took a new turn in the second half of the twentieth century. With the outbreak of the Second World War, the tile along with many other objects was removed from Berlin and stored in a salt mine in Grasleben for safekeeping. After the end of the war, the tile was sent to the Zonal Fine Art Repository in Celle. We can follow its path in the ‘Islamic Art’ exhibition held in 1947 in Schloss Celle, a castle in Lower Saxony, where it was once again labelled ‘Spanish Tile from Malaga’.

In 1954, when the tile returned to Berlin, the city was divided into East and West Berlin. Along with the city’s division the museum collections were also split. Some museums were duplicated and so-called twin museums were now located in both parts of the city. While the Pergamon Museum was in East Berlin, the tile having remained in West Germany after the war, now entered the Museum für Islamische Kunst in West Berlin. In 1967, director Klaus Brisch and curator Johanna Zick-Nissen prepared a new exhibition at Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin. The accompanying catalog attributes the tile to Iran and dates it to the thirteenth century.

A few years later, in 1971, the Museum für Islamische Kunst in West Berlin moved to a new building in Dahlem, where the tile was again displayed.

With the reunification of the two German states in 1990, the twin museums were reunited. The collection was presented in a new permanent exhibition at the Pergamon Museum, which opened in 2000.

How and when did the tile travel from Iran to Seville?

The provenance research ideally provides complete information about the object from the creation of the work of art to the present day. However, there is still a gap in the provenance chain regarding the question of when and how the tile came from its place of origin in Iran to Seville, Spain. This gap has recently been partially filled. A photograph from the 1880s, now kept at the Getty Research Institute, shows a cabinet belonging to a private collector in his home in Tehran, Iran. The cabinet is filled with luster ceramics from different times, including the mihrab tile. The collector presumably sold the ceramics on at some point and at least one of the pieces, namely the tile, travelled to Seville, where Julius Lessing acquired it in 1900.

At the end of the nineteenth century, luster ceramics from Iran and Spain were equally sought after by collectors and museums in Europe and the United States. A well-organized network of national and international dealers ensured that the artworks were transported and sold to an interested clientele. Today, researchers around the world are trying to reconstruct the original contexts of tiles such as this one, whose original building remains unknown. Unfortunately, the back of this tile does not reveal any additional information so more detective work is required to reveal the entire path of the tile.

About the author

Deniz Erduman-Çalış

Curator, Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin

With special thanks to Keelan Overton, Miriam Kühn, Farwah Rizvi and Maximilian Heiden

Sources

- Inventory log of the Museum für Kunstgewerbe Berlin, 1899-1900, https://storage.smb.museum/erwerbungsbuecher/EB_KGM-K_SLG_LZ_1899-1900.pdf

- n.a. “Islamische Kunst. Ausstellung des Museums für Islamische Kunst.” Schloss Charlottenburg (Langhansbau) Berlin, 1967. (exhibition catalog)

- Erdmann, Kurt. “Islamische Kunst.” Schloss Celle (Central Repository), 1947. (exhibition catalog)

- Erduman-Çalış, Deniz. Faszination Lüsterglanz und Kobaltblau. Die Geschichte Islamischer Keramik in Museen Deutschlands. München: Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, 2020. [LMU]

- Erduman-Çalış, Deniz. “Berlin, Germany: Tile in the form of an arch.” Luster cabinet entry in The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: An Online Exhibition of an Iranian Shrine, directed and edited by Keelan Overton. 33 Arches Productions, January 15, 2025. Host: Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online.

- Kühnel, Ernst. “Die Ausstellung islamischer Kunst im Haag.” Der Kunstwanderer (1926/27): 493-496.

- Masuya, Tomoko. “Persian tiles on European walls: Collecting Ilkhanid tiles in Nineteenth-Century Europe.” Ars Orientalis 30 (2000): 39–64 [JSTOR]

- Sarre, Friedrich. “Die spanisch-maurischen Lüsterfayencen des Mittelalters und ihre Herstellung in Malaga.” Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 24, 2 (1903): 103–30. [JSTOR]

Related Stories

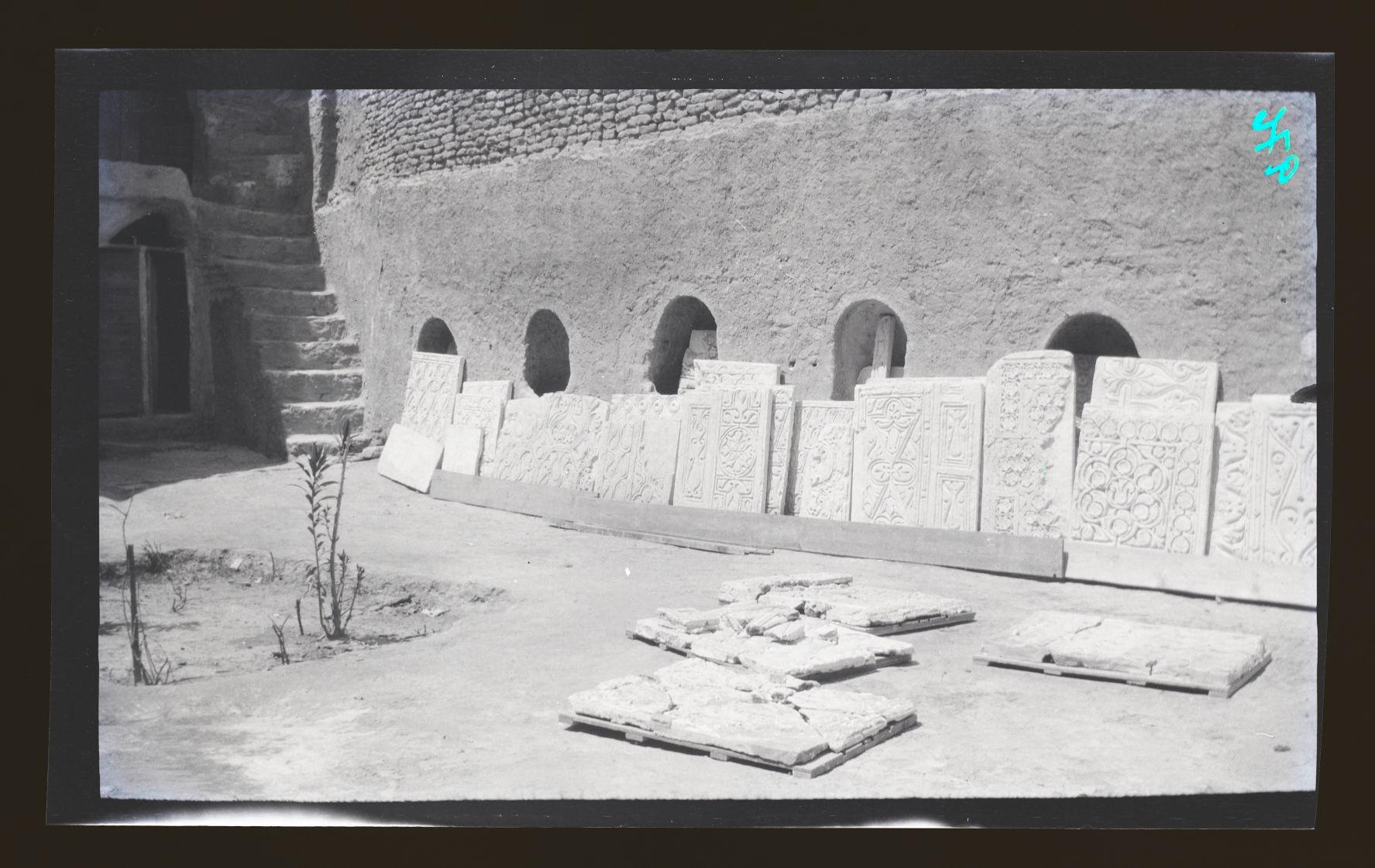

From Samarra to Berlin

The provenance of stucco decorations from the caliphs' residence in Samarra to the Islamic section of the Royal Museums in Berlin.

Crossroads Iran

Crossroads Iran highlights narratives with Iran at the crossroads of cultural exchange and artistic influence. This initiative connects museum objects with archival photos, through stories and videos.

Our favorite objects

Our team has handpicked their favorite objects and are sharing their personal connection with them. Join us on this special journey as we unveil new insights from our collection.

Europeans in a Persian blue and white pottery

Global trade and its dynamics. Motifs of Chinese and European art on blue and white ceramics from Iran.