en

- de

- en

About the Story

Researching the origin (provenance) of its collection is one of the core tasks of a museum. Some of the artefacts from the excavations in Samarra (today’s Iraq) at the beginning of the 20th century found their way to Berlin. Today, the archaeological artefacts are kept and researched in the Museum for Islamic Art of the National Museums in Berlin (formerly the Islamic Department of the Royal Museums in Berlin). In this story, let’s look at how the stucco decorations that adorned the buildings of the caliph's residence in Samarra on the Tigris travelled to the river Spree.

Where is the Samarra archaeological site located?

Samarra was under Ottoman control until 1917 and belonged to the province of Baghdad (Vilâyet Baghdad). It is located on the river Tigris, and is 125 km north of today's Iraqi capital Baghdad.

Why was Samarra such an important place?

Samarra held a significant place in the history of Islamic civilizations. The eighth caliph of the Islamic Abbasid dynasty al-Muʿtasim (reigned: 833-42) founded the residential city of Samarra in 836, temporarily replacing Baghdad as the seat of government. As the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate during its zenith, the city played a pivotal role in shaping the political, cultural, and intellectual landscape of the Islamic world. During this era, Samarra became a hub of culture, learning, and innovation. Today, the ruins cover an area of over 50 km2 and include several palaces and mosques as well as numerous residential buildings.

Who excavated in Samarra between 1911 and 1913?

The ruins of Samarra were among the first systematically researched and documented Islamic period archaeological sites of their time. Between 1911 and 1913, the architect and archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld (1879-1948) investigated the site in two excavation seasons.

Who had an interest in the excavations in Samarra at the beginning of the 20th century?

The excavations in Samarra were primarily funded through private means, including contributions by Friedrich Sarre (1865-1945), head of the Islamic Department, and Wilhelm Bode (1845-1929), Director General of the Royal Museums in Berlin. Although the excavations were carried out as a private endeavour by Friedrich Sarre, the finds were intended for the benefit of the Berlin museums. At this time, the Royal Museums were already involved in several archaeological undertakings in the Ottoman Empire and feared that they would not receive a license for the excavations in Samarra from the Ottoman authorities if they were to be an official museum undertaking.

This is why the excavations in Samarra, unlike those in Assur and Babylon at the same time, which were organised by the German Oriental Society in Mesopotamia, were launched as a private venture by Sarre. He partly financed it himself, but members of his family and contacts in his network were also involved as donors.

What was the legal framework in 1911/1913?

To understand the processes involved in excavation and transfer of excavated materials outside the region, we have to look at the legal framework in place at the time of the excavation. Foreign interested parties could acquire licenses in the Ottoman Empire for the purpose of excavating, as Friedrich Sarre did for Samarra. However, these licenses were not transferable. In addition, the Antiquities Act of 1906 (Art. IV) did not permit the export of archaeological artefacts from the Ottoman Empire.

Halil Edhem Bey (1861-1938), the Director General of the Imperial Museums in Constantinople (now Istanbul), who was responsible for archaeological artefacts in the Ottoman Empire, helped to draft this law.

Introduction of the persons

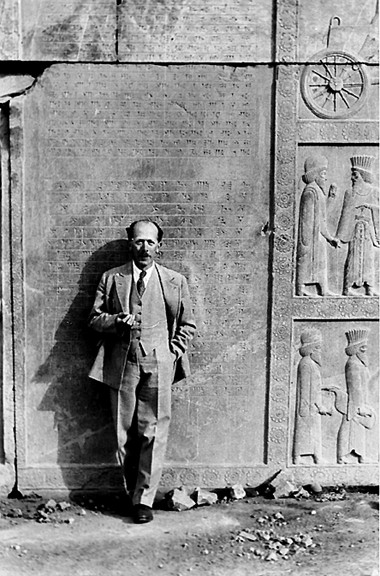

Ernst Herzfeld (1879–1948)

Ernst Herzfeld (1879-1948) was a German architect and one of the first researchers in the field of Islamic archaeology. In addition to his research in Mesopotamia, he was also intensively working on the cultures of ancient Persia. As early as 1907/08, he undertook a research trip through the Euphrates-Tigris region (today’s south-east Turkey, Syria and Iraq) together with Friedrich Sarre. Following this, Samarra emerged as a promising location for archaeological field research and Ernst Herzfeld became its field director.

Friedrich Sarre (1865–1945)

Friedrich Sarre (1865-1945) was a German art historian and art collector. From 1904 he headed the newly founded Islamic Department of the Royal Museums. Thanks in part to his marriage to his wife Maria (née Humann), the daughter of the excavator of Pergamon Carl Humann, Friedrich Sarre was well connected in the archaeological world of the time. In 1907/08, he undertook a research trip to the Euphrates-Tigris region (today’s south-east Turkey, Syria and Iraq) with the architect Ernst Herzfeld, which he financed, in order to select a promising excavation site.

Wilhelm Bode (1845–1929)

Wilhelm Bode (1845-1929), later also known as Wilhelm von Bode, was a German art historian and since 1905 Director General of the Royal Museums in Berlin. He founded the Islamic Department in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in 1904. He also provided financial support for the excavations at Samarra (1911-1913).

Halil Edhem Bey (1861–1938)

Halil Edhem Bey (1861-1938) was the general director of the Imperial Ottoman Museums in Constantinople (1910-1931) during the excavations in Samarra. He was the younger brother of the archaeologist and painter Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910) and his successor. He had a long private friendship with Friedrich Sarre and his wife Maria Sarre.

Photos: Ernst Herzfeld 1925 in Persepolis. Photo: Henry Breasted jr. (gemeinfrei / public domain),

Friedrich Sarre around 1894. Photographer unknown, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Islamische Kunst,

Wilhelm von Bode. SMB-ZA, V-Slg. Personen, Bode, W. v,

Halil Edhem Bey around 1910. Photo: Anonymous (gemeinfrei / public domain)

What finds came to light in Samarra in 1911-13 and what happened to them?

During the excavations in Samarra, a large number of ornamental stucco panels that once adorned the walls of various buildings came to light. The originals were removed from the walls and plaster casts were made of them in order to study and preserve their variations and motifs and to be able to present them later in the museum.

This work was carried out by two plaster technicians from the Royal Museums in Berlin, Theodor Bartus and Karl Beger, who also sawed the stucco decorations out of the walls or completely destroyed the mud brick walls in order to access the decorations. They then produced clay moulds from which the plaster casts were made. However, this method also resulted in some of the original slabs breaking. In total, around 300 wall decorations were removed between 1911 and 1913. The applicable Antiquities Act of 1906 (Art. XVI.3) allowed foreign excavators to make plaster casts, which could also be transported out of the country.

Introduction of the Persons

Find out more about the plaster technicians at the Royal Museums in Berlin.

Theodor Bartus (1858–1941)

Theodor Bartus (1858-1941) was an assistant restorer at the Berlin Ethnological Museum from 1888 and also took part in the Turfan expeditions organised by his museum. He was involved in the 1st excavation season in Samarra from October to December 1911.

Karl Beger (1867–1930)

Karl Beger (1867-1930) worked in the plaster moulding department of the Royal Museums. He took part in the Samarra expedition during the 2nd excavation season from February to May 1913. He later also worked at Tell Halaf as a plaster technician for Max von Oppenheim.

How did the stucco decorations get to Berlin?

After the excavations in Samarra were completed, the casts and originals of the stucco decorations, along with other finds, travelled by river, sea and rail to the Islamic Department of the Royal Museums in Berlin. According to Friedrich Sarre, these included around 30 examples of the original wall panels and around 60 casts.

How were the stucco panels integrated into the collection of the Islamic Department?

In November and December 1921, both the originals and the plaster casts of the stucco decorations were inventoried in the museum and registered in the acquisitions book of the Islamic Department. They are listed there under the numbers I. 3467 to 3547 and I. 4524 to 4528.

And what happened afterwards?

After being transported, most of the original stucco decorations and many of the casts arrived at the museum broken and first had to be restored. In 1922, some of them were placed in the exhibition rooms of the Islamic Department in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (now the Bode Museum) and staged for visitors for the first time.

Legal – Illegal?

In 1922, Ernst Herzfeld mentions in a document the illegal export of finds from Samarra from the Ottoman Empire. These included a number of original stucco decorations, about which he wrote:

"In his time, I have attributed originals to a large number of casts, and Professor Sarre has obtained subsequent authorisation for this through his good relations with the Ottoman museums. So today we also own the originals de jure, whereas the museums were only entitled to casts."

And now?

The circumstances surrounding the excavations in Samarra between 1911 and 1913 and the transfer of the finds to Berlin are currently being investigated at the Museum for Islamic Art as part of the "Legal - Illegal?" project. This is a cooperation project with the Research Center for Anatolian Civilisations (ANAMED) at Koç University in Istanbul, which was initiated by the Central Archive of the National Museums in Berlin. In comparison with excavations from other collections of the National Museums in Berlin (Samʼal - Museum of the Ancient Near East and Didyma - Collection of Classical Antiquities), a comprehensive guideline for handling archaeological collections from scientific excavations in the Ottoman Empire is to be developed.

Original or cast? Can you find out!?

At first glance, it is not easy to distinguish between the original stucco decorations and their mouldings. This fact was also used to transport the original wall panels out of the Ottoman Empire unnoticed.

In 2012, as part of the project "Samarra and the Art of the Abbasids", scientific investigations were carried out to solve the mystery. The results of this research were integrated into the museum database of the National Museums in Berlin. Here you can find out for yourself which wall decoration is an original or a copy. If you would like to know more about Samarra and the Museum for Islamic Art, why not take a look here.

About the Author

This article was written by Stefanie Janke, employee of the “Legal - Illegal” project for Provenance Research Day 2024.

Related stories

DIGITALISING SAMARRA

All of the 1.500 or so preserved photographs of two excavation campaigns are now available for the first time.

VOICES AND MEMORIES OF SAMARRA

Voices from Samarra sharing their memories and wisdom with us.

From Samarra to Berlin

The provenance of stucco decorations from the caliphs' residence in Samarra to the Islamic section of the Royal Museums in Berlin.