en

- de

- en

This online exhibition explores issues of partition and completion, preservation and destruction, remembrance and forgetting. It was created as part of the special exhibition In:complete. Destroyed - Divided - Completed (on view at the Kunstbibliothek, Sept. 30, 2022 to Jan. 15, 2023). It combines objects from 23 museums within the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz from prehistoric times to the present.

un:protected ♦ How can museums protect their artworks from destruction? un:important ♦ What does a museum collect and how does it preserve their objects for future generations? un:known ♦ Do museums only display masterpieces and authentic testimonies of the past? un:seen ♦ When is a work of art considered "complete"? un:usable ♦ What does collecting do to objects and according to which criteria do they become parts of museums? un:forgettable ♦ How do we understand art in the age of reproduction?

And what about in art history?

Broken stories

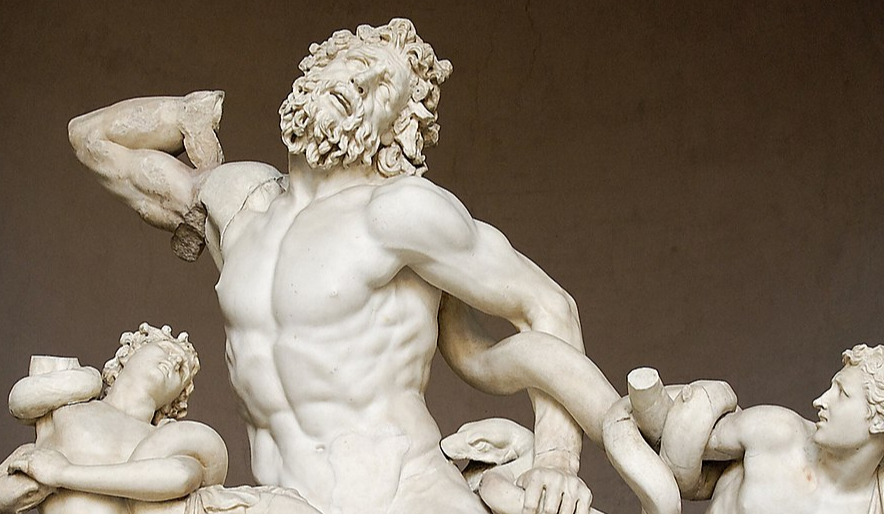

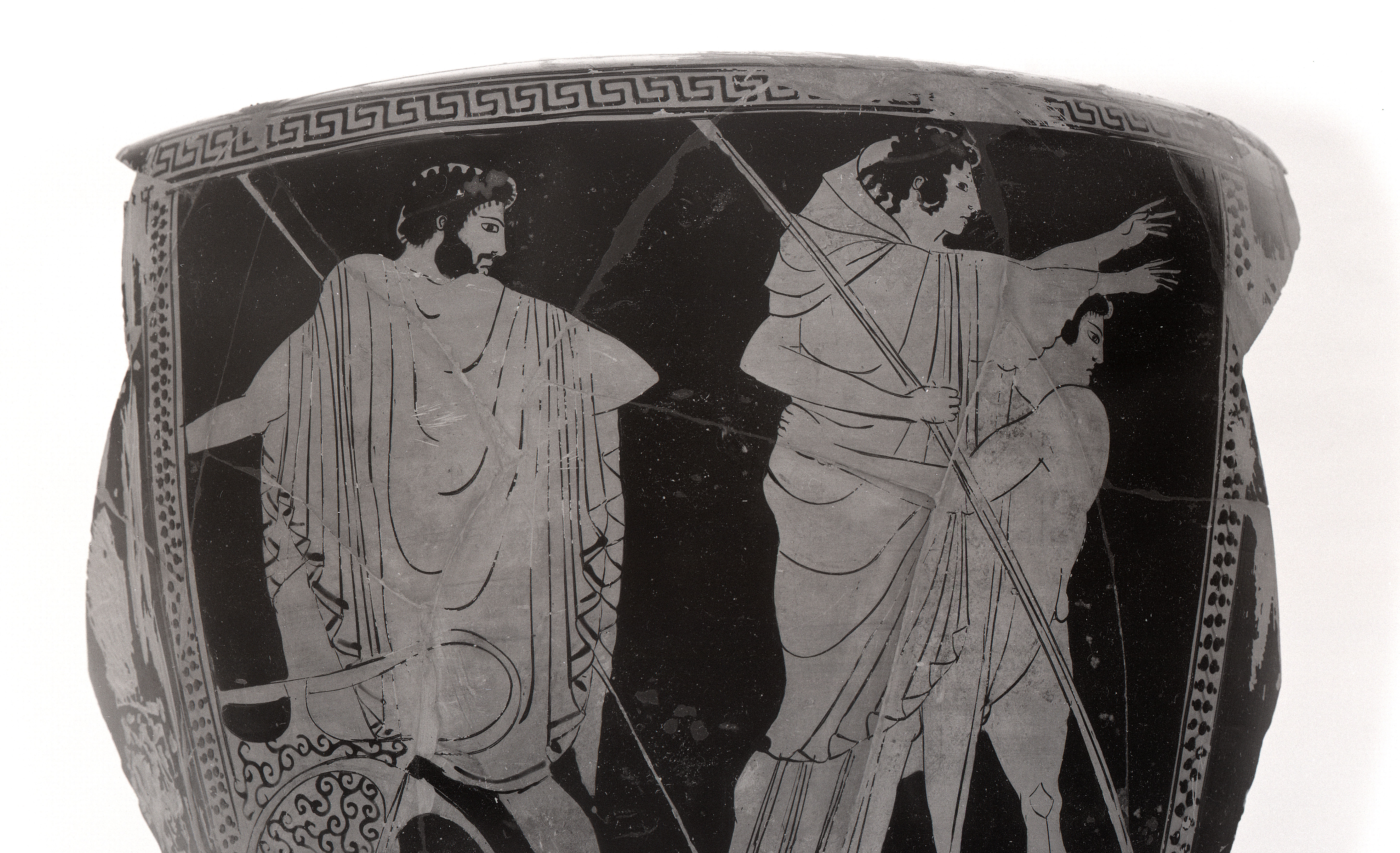

The Laocoon group is one of the most famous ancient works of art and can be admired today in the Vatican. It shows a mythological scene in which Laocoon, a priest from Troy, and his two sons are attacked by sea serpents. The snakes were sent by a god as punishment. For what? There are several versions: In some stories, it is punishment for his marriage and thus failure to observe celibacy. In other accounts, it is associated with the story about the Trojan horse, whose deception Laocoon had recognized.

Powerful or exhausted?

When a fragment changes the image of masculinity....

The Laocoon group was discovered in Rome about 1500 years after its creation in 1506. However, there was a blank space: the right arm was missing, leaving room for interpretation.

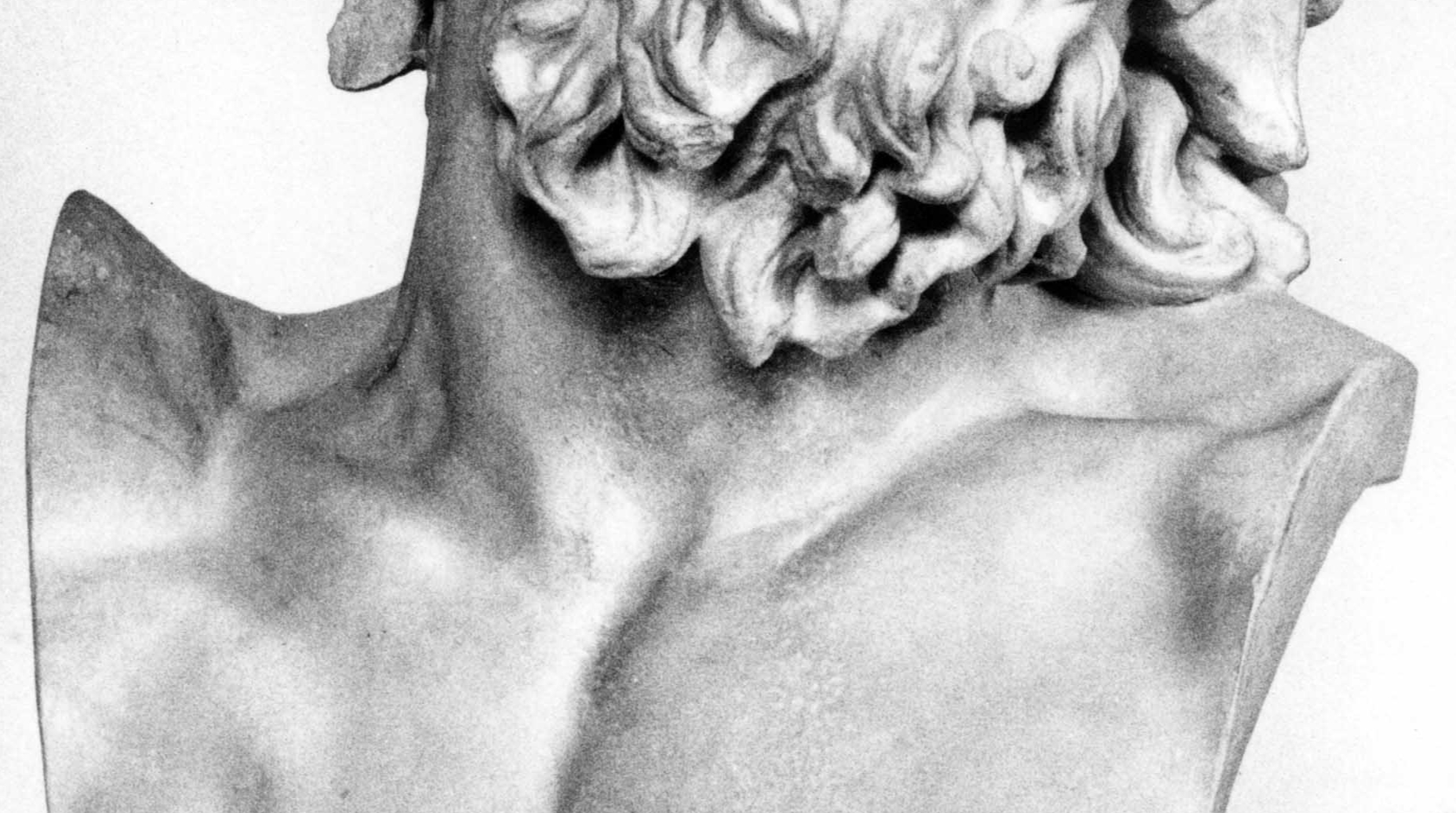

In 1532, it was supplemented by the Renaissance sculptor Montorsoli with a powerfully outstretched arm holding the snake away from the body. In 1903, however, the original arm was found, not raised but bent.

And then?

For several hundred years, the outstretched arm characterized the overall appearance of the sculpture. Then the "original" emerged and it became comprehensible how the ancient artist had conceived Laocoon. What does this do to the Renaissance interpretation?

The man who still appears powerful even in battle became a less heroic Laocoon: a man who is rather exhausted and almost defeated.

Plaster fragments

In the Gipsformerei ...

of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, both versions of the Laocoon group are offered in plaster. And not only these, also fragments, such as the bust of Laocoon, the heads of his sons or an acanthus leaf of the priest can be ordered there from plaster.

Works of art, or even parts of them, are thus duplicated and can be placed in other contexts. Would you also like to have an arm of Laocoon?

Laokoon fragments in the Gipsformerei Berlin

Laocoon group in 3D

10 plaster models that tell art history

What's the point of plaster art? We want to see the originals, don't we?

The memory of museums

The Gipsformerei is the oldest institution of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. In 1819 it was founded as the "Königlich Preußische Gipsgussanstalt" (Royal Prussian Gypsum Casting Institute). Plaster casts have multiple functions: they serve artistic studies, as templates for repairs, and commercial sales. After all, such a plaster cast can look quite decorative. But we also sometimes find plaster casts in museums. For example, the Altes Museum on Museum Island, founded in 1925, was initially completely filled with plaster casts.

The Gipsformerei survived the Second World War intact. For the memory of some works, this was a stroke of luck. Around 500 casts of works of art whose originals had been damaged or destroyed were stored there.

Thus, although the plaster casts are not originals, they are valuable for their preservation.

Original or copy?

The plaster casts of Laocoon or individual parts of the sculpture are in demand, even if they are not the original. But there are other objects for which the status of "original" is extremely important.

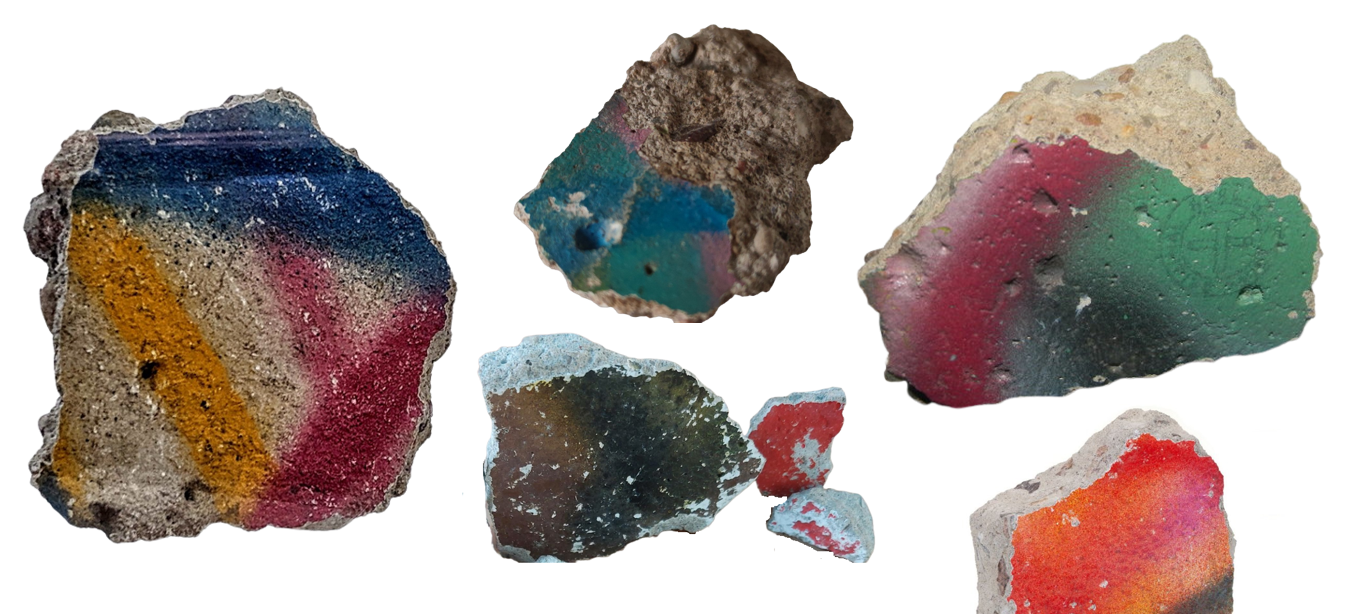

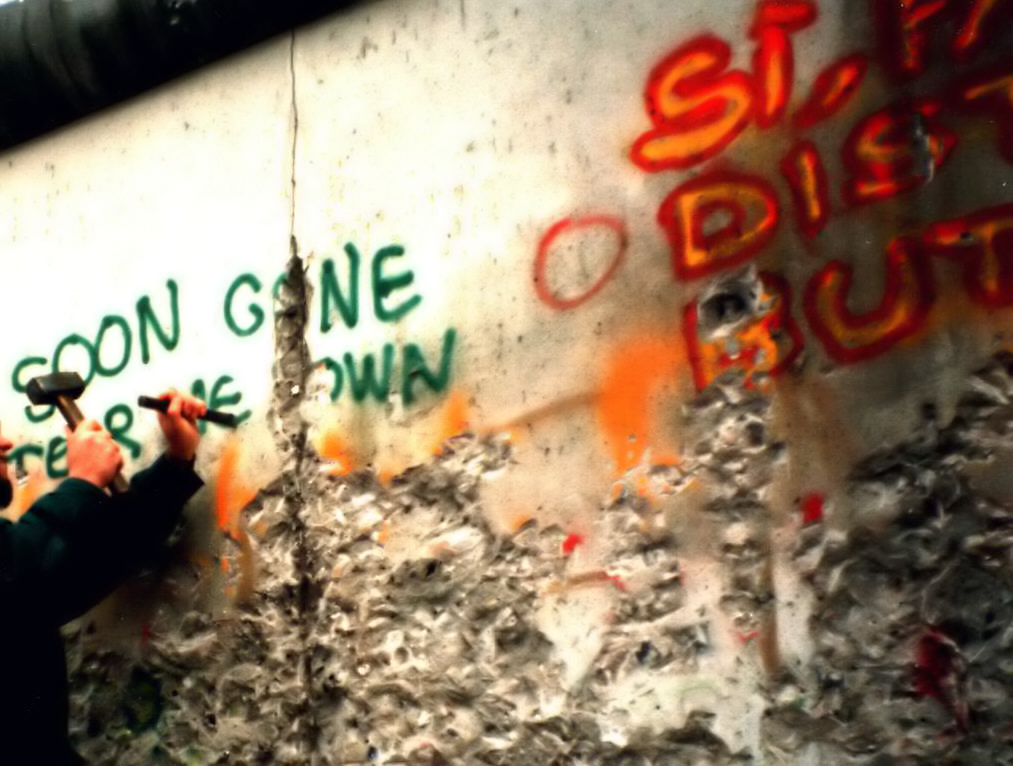

Fragmentation of the wall

Woodpeckers

After the Berlin Wall was overcome without violence on November 9, 1989, it was literally dismantled and fragmented. Thousands of people knocked out larger and smaller pieces. People were soon talking about wall woodpeckers. The fall of the Wall changed the meaning of the concrete, which now became a symbol of freedom.

The fragments, however, served not only as personal souvenirs, some also tried to sell them as a fragment of history. To this day, pieces of the wall can be purchased at flea markets or on the Internet. Certificates are supposed to vouch for their authenticity.

But whether they are really genuine, who knows...

Real?

Some fragments were also further processed. Like this wall earring, which is now kept in the Museum Europäischer Kulturen - with certificate of authenticity!