en

- de

- en

This online exhibition explores issues of partition and completion, preservation and destruction, remembrance and forgetting. It was created as part of the special exhibition In:complete. Destroyed - Divided - Completed (on view at the Kunstbibliothek, Sept. 30, 2022 to Jan. 15, 2023). It combines objects from 23 museums within the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz from prehistoric times to the present.

un:protected ♦ How can museums protect their artworks from destruction? un:important ♦ What does a museum collect and how does it preserve their objects for future generations? un:known ♦ Do museums only display masterpieces and authentic testimonies of the past? un:seen ♦ When is a work of art considered "complete"? un:usable ♦ What does collecting do to objects and according to which criteria do they become parts of museums? un:forgettable ♦ How do we understand art in the age of reproduction?

For real?

Original

An "original" is an unaltered work created by the artist himself or herself.

So, we might go to a painting gallery to see a real Van Gogh. The originals have a special aura - quite different from their reproductions that can be seen in books or on the internet.

In archaeological museums, you can mainly see (art) objects found in the ground that have been excavated by archaeologists. Often the creators are not known. But the originals bear witness to techniques and tastes from a past era.

Pasticcio

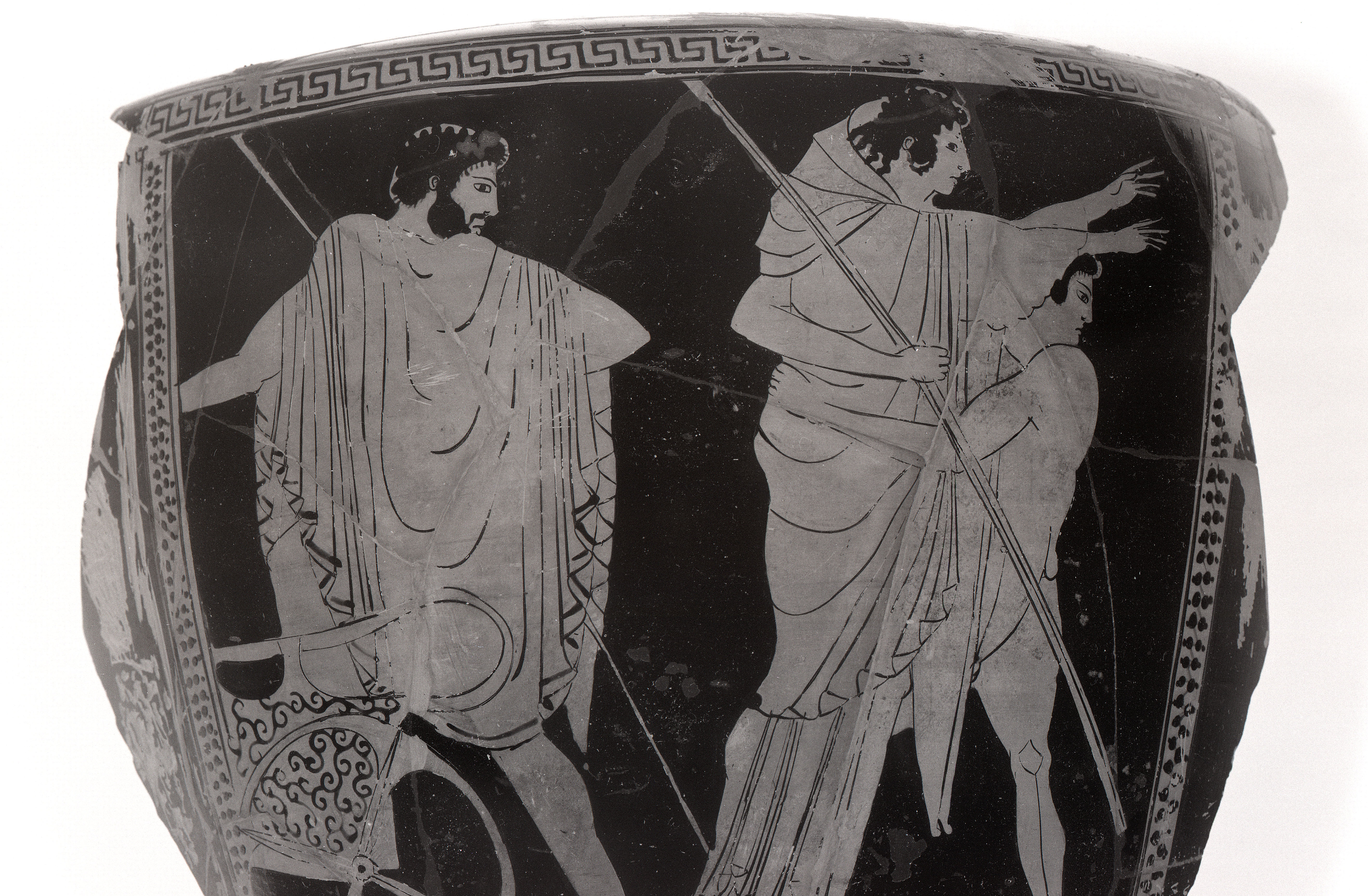

In the 18th and 19th century, antique fragments that did not belong together were often assembled into new vessels. The more complete an object was, the better it was sold and exhibited. Such a composite work is called a pasticcio (plural pasticci).

Pasticci are not always recognisable at first glance. But when restorers discover one in their collection, they have to take decisions: do they leave the assembled object as it is or do they deconstruct it into its individual parts?

In the case of the vase from the Antikensammlung, they decided to separate the picture field from the body of the vase, which originally did not belong together. In this way, the two fragments can be experienced separately again - even though they are connected by their history.

But the pasticci can also still be exciting today: they tell of the imagined idea of antiquity in the respective time and are important sources on the history of restoration in 18th- and 19th-century Europe.

Addition

Often in the 19th and early 20th century, original fragments from archaeological excavations were also completed by modern additions. This was done very creatively: Technique, colour and decoration were imitated as faithfully as possible and fired into the appropriate shape.

One reason was certainly that complete vessels fetched a higher price on the market. But the additions also tell of a changing aesthetic, which at a certain time preferred the complete impression to the fragmentary one.

Whether they are forgeries is debatable: the additions are often clearly recognisable as not approaching the original in quality. But how many additions have remained undiscovered so far?

Today, this bowl has been "de-constructed": it has been disassembled into its individual parts and the original fragments separated from the later ones. The addition is now kept obvious, so that it is immediately recognisable what is original.

The removed hisotrical addition is still kept in the museum storage room- perhaps one day it will itself become an exhibition object that tells of the restoration ethics of the 19th century.

Forgery

Time and again, the police, with the help of experts, come across forgeries. Fakes are often difficult to recognise and sometimes make it into exhibitions and museum collections. Only those who know the works of the imitated artists very well can distinguish a fake from the original.

In this case, the forger Leonhard Wacker, who painted "Reaper in the Cornfield" in the manner of Van Gogh, was convicted because he made a design for his forgery, which he signed himself... Comparative X-ray examinations between the original and the forgery were introduced into the criminal proceedings.

The old-fashioned look

Forgeries occur in every materiality. Not only paintings, but also objects made of stone, wood, metal or ceramics can be forged. Old art objects are often imitated because they are particularly valuable. Certain techniques, like acid baths, make the fake look very old.

The figurative vessel of a goddess gained fame when it appeared on a stamp of the Deutsche Bundespost Berlin in 1984. A few years later, the Rathgen-Forschungslabor determined during a thermoluminescence examination that it was a fake.

Reproduction

The Berlin museums also hold reproductions of art objects. There are various reasons for this.

The Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte has reproduced a very special group of objects because they were lost:

The "Treasure of Priam" was taken to Russia in 1945 as war booty, where it remains until today in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.

Reconstruction

If an art object has not survived the test of time, there are various ways to reconstruct it. Perhaps there are old descriptions, illustrations or photographs.

Sometimes the idea for a work of art was never put into practice. In this case, sketches or designs by the artists can help reconstruct a work of art that the creators themselves never got around to.

Reconstruction of a model designed by Rudolph Belling

Students of Model + Design at the Technische Universität Berlin have reconstructed Belling's models based on his designs and built them out of papier-mâché, wood, metal and styrodur. Thus, Belling's designs can now be experienced, although they never existed in 3-D.

Copy

Not every duplicate is a forgery: there are also quite a few official copies of art objects.

A copy is a one-to-one duplication of the original. Three-dimensional objects, however, cannot simply be put on the copier.... There is the method of plaster casting - but this is no longer done today to protect the objects.

The famous Uruk vase in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, for example, is a copy for which the cast was taken right at the time of the excavation in 1933, when the vase was found.

The original is now in the museum in Baghdad. The vase creates an exciting connection between Iraq and Berlin and shows how many stories even a copy can tell.