en

- de

- en

This online exhibition explores issues of partition and completion, preservation and destruction, remembrance and forgetting. It was created as part of the special exhibition In:complete. Destroyed - Divided - Completed (on view at the Kunstbibliothek, Sept. 30, 2022 to Jan. 15, 2023). It combines objects from 23 museums within the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz from prehistoric times to the present.

un:protected ♦ How can museums protect their artworks from destruction? un:important ♦ What does a museum collect and how does it preserve their objects for future generations? un:known ♦ Do museums only display masterpieces and authentic testimonies of the past? un:seen ♦ When is a work of art considered "complete"? un:usable ♦ What does collecting do to objects and according to which criteria do they become parts of museums? un:forgettable ♦ How do we understand art in the age of reproduction?

When museums make a selection...

Museums collect things that seem worthy of preservation at certain times. Not infrequently, these are taken out of their specific contexts. Musealization and fragmentation frequently go hand in hand. Robbed of their everyday contexts, objects are given a new order by museums. Certain aspects receive special attention, others are barely registered. Here we present two objects from the exhibition "in:complete" for which this is particularly true. They exemplify the fact that a large part of our knowledge about cultural spaces or caesuras is based on selection processes taking place in museums.

Who collects such things?

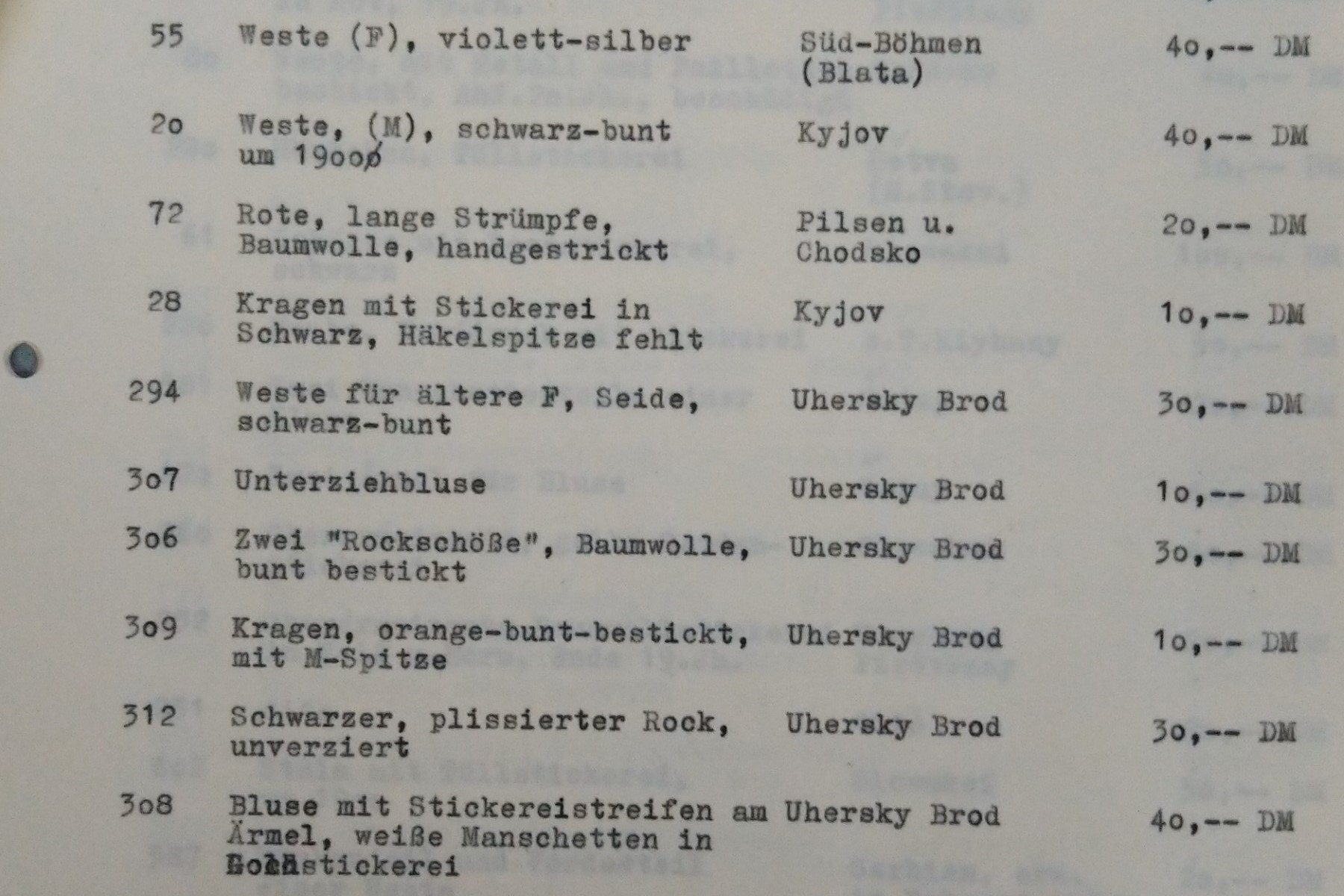

During the 1970s, the West Berlin Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde (one of the predecessor institutions of today's Museums Europäischer Kulturen) acquired a large number of Czech and Slovak shirt and collar embroideries. Entirely "unusable", apparently, were the uncollected backing fabrics. They were simply considered unimportant for the intended systematization of embroideries into regional types. The characteristics of the embroideries served primarily to group textiles into certain "costumes". Such and similar strips can be found in many ethnographic museums in the Czech-Slovak border region.

Where does it come from?

It was not only museums that considered parts of objects "unusable". Embroideries like these were often made by the rural population and attracted the interest of collectors from the urban centers. In search of products of the supposedly "untouched" country life, the collectors arrived in large numbers in the peripheries from the late 19th century onwards. The local population took advantage of this and sold their old embroideries, for which they often no longer had much use themselves. Carefully cut out, the carrier textiles could be put to further use.

If only a part of the object ends up in the museum ...

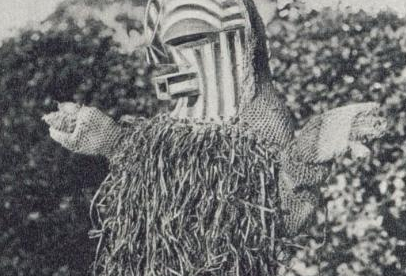

This headpiece is part of a larger Bifwebe-mask, as they were used in some regions of today's Democratic Republic of Congo. Several such masks are kept in the collection of the Ethnological Museum. The headpiece is in fact only a component of the dance masks - these also consisted of capes and other parts of the twill.

... it cannot tell its story

However, since the European collectors were mostly not interested in these components, often only the parts of the face were collected. In the museums of the colonial metropolises, these fragments were admired as "sculptures" - the other parts were usually of no interest to them.

For their makers, they were thus deprived of their context and literally "un:usable".